Thanks for reading Maynard’s War, and a warm welcome to my new subscribers. Chapter 23 will be published next Sunday, 18th May at 11am UK time. Do please share with anyone you think might be interested - it takes but a click.

If you’ve only just discovered Maynard’s War and would like to start at the beginning, then please click this button:

December 1916

Predictably, the Lansdowne memorandum had found little support in Cabinet. Asquith and his small band of loyal lieutenants insisted it be given a hearing and congratulated Lansdowne on the logic of his argument. Keynes wondered if the Prime Minister would have taken things further if he’d had the support of more of his ministers, but it was difficult to see how any offer of talks with the Germans would be made in any case. The Americans were standing by to act as mediators, but despite the efforts of Colonel House to play up the prospects of a negotiated settlement in public, Keynes knew from their private conversations that he was far from convinced by the Germans’ overtures.

Lloyd George, from his position at the War Office, was expanding his power base with indecent haste. Not only did he have the support of the press, but the generals adored him and he was making a great many friends among senior Conservatives. Keynes had long thought him a Liberal only for reasons of expediency: He would do whatever was necessary to get what he wanted, regardless of the demands of party loyalty.

From what he could glean, the Lansdowne episode had served further to weaken Asquith’s position just as he appeared to be recovering his appetite for politics after the death of his son. Following a conversation with Edwin Montagu earlier in the day, Keynes had decided to set aside a couple of hours for contingency planning: the contingency being that Asquith might not be Prime Minister for very much longer.

It was difficult to gauge the severity of the threat. Asquith only enjoyed minority support in cabinet, but it seemed unlikely that Lloyd George would be able to form a government. Many who supported his approach to the war baulked at the thought of the Welshman becoming Prime Minister. Like Keynes, their dealings with him had left a bad taste.

There was a knock on the door and Montagu entered. “Have a seat Edwin,” Keynes said. “Is it too early to offer you a sherry.”

“Probably, but pour me one anyway.”

“I take it you have news from the front line.”

“Yes. The Lloyd George offensive is underway.”

“By what means?”

“He’s demanding the establishment of a three-man committee to run the war.”

“Presumably not including the Prime Minister?”

“Exactly.”

“Asquith won’t go for that.”

“Apparently he’s thinking about it, on condition that he can attend as an observer.”

“But it would undermine his authority in Cabinet completely.”

“It would. He must be gambling on the fact the Lloyd George doesn’t have enough support to form a government himself.”

“Why do you think Lloyd George has made his move now?”

“I saw Northcliffe going into his office last evening. I presume he’s been given the go-ahead.”

Keynes shook his head. It appalled him the extent to which the press, and Lord Northcliffe in particular, was able to dictate terms to the Government.

“Surely, if Lloyd George is going to run the war Asquith might as well stand aside,” Keynes suggested.

“You know him as well as I do, Maynard. He’s a very proud man. He feels responsible for not preventing the slide to war. He wants to see it through.” Montagu knocked back the rest of his sherry. “I’ll let you know if anything else comes up,” he said, closing the door behind him.

Keynes didn’t see Montagu again for several days. His next appointment, the following morning, was with the Prime Minister, whom he found in sombre but determined mood. “Thank you for coming over at such short notice Keynes. I’ve always valued your advice. It’s a political rather than a financial question on this occasion, but it could well have an impact on your department, so I wanted to keep you informed.”

“Of course, Prime Minister. Thank you.”

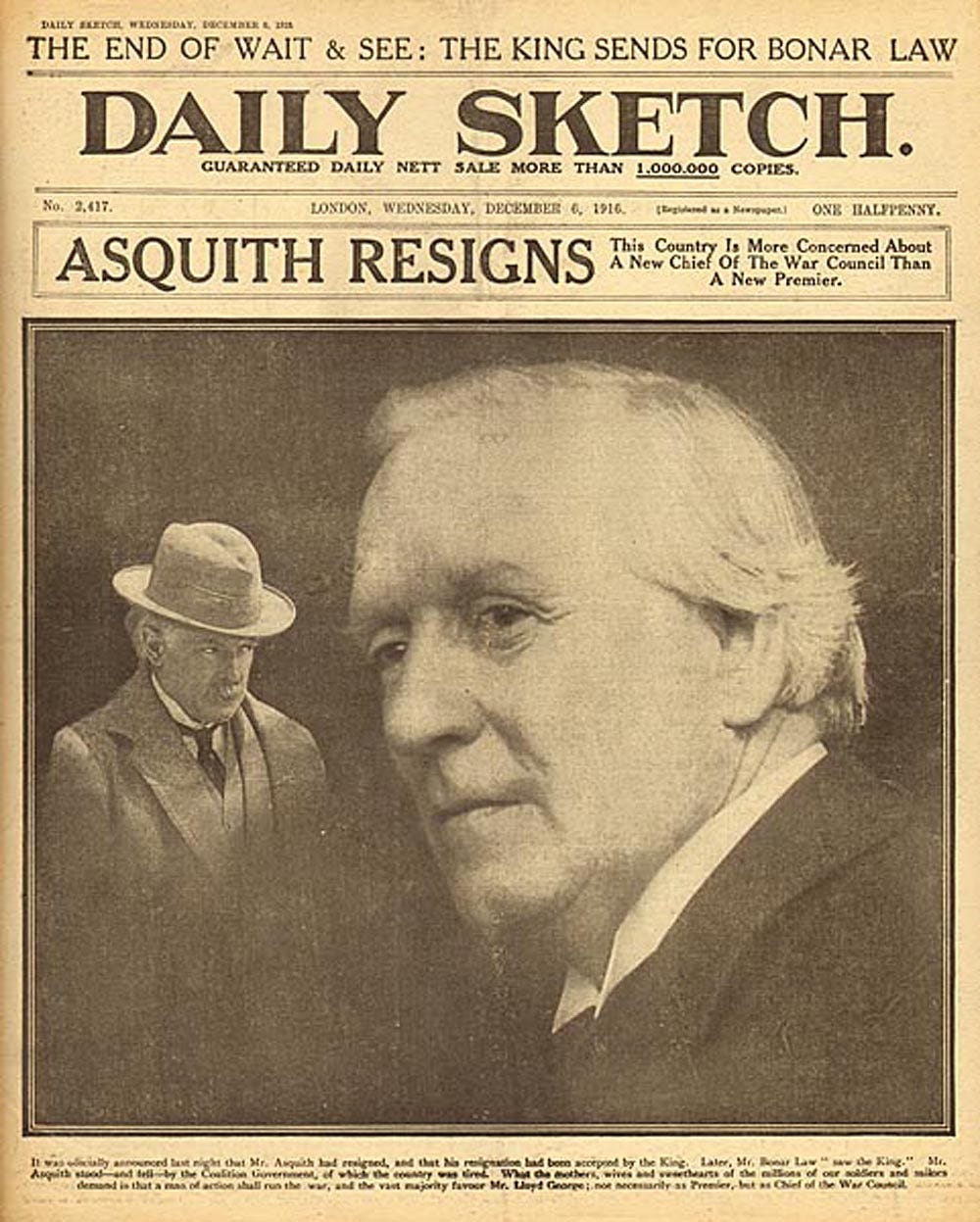

“As you’ve no doubt heard, Lloyd George has resigned.”

“Yes. A considerable loss for the government from what I read in the early editions of the Evening Standard.”

“Do you still read the papers Keynes? I’m afraid I find them so full of things I know to be untrue that I no longer bother.”

“Yes, Prime Minister.”

“A case in point being this dreadful piece in today’s Times,” He passed the newspaper across the desk, opened to the page where, under the headline ‘Time for a new man at the helm’, it had explicitly called for Asquith’s resignation and his replacement by Lloyd George.

“Montagu said he saw Northcliffe at the War Office.”

“Yes, well. I had been inclined to work with Lloyd George on his plan for a reconstituted war committee, but when I read this, obviously that was no longer possible. When I told Lloyd George he turned an interesting colour and stormed out. I received his letter of resignation an hour later.” Asquith briefly lifted an envelope from his desk before letting it fall.

Everything about the Prime Minister suggested to Keynes that he knew this apparent victory was anything but. “And your next move?” he asked.

“I think it’s time to call his bluff. I’m sick of his people, none of them have the courage to criticise me to my face.”

“I see,” Keynes was impressed by the Prime Minister’s conviction, but unsure what strategy it might bring forth.

“I’m going to resign, Keynes. My opponents will then be revealed for what they really are. None of them will be able to form a government. The King will have no option but to turn back to me. Then I can move Lloyd George out of the War Office.”

“As long as you don’t send him back to the Treasury, Sir, and as long as you are sure you can depend on the loyalty of your own people, then it sounds like a good plan. And it’ll show the country what a strong leader you are.”

“It’s in the numbers Keynes. There’s no way Lloyd George can form a government. I’d bet my house on it.”

“And who might replace him at the War Office?” Asquith smiled at the question and Keynes was unsure if he was going to answer.

“I thought I might give it to Lansdowne. What do you think?”

“His record speaks for itself. A most capable and experienced politician.”

“And one whose name is synonymous with the idea of peace.”

“If anyone can negotiate an end to the war, it is Lansdowne.”

Keynes left Asquith’s office with a bounce in his step: not only had he been taken, once again, into the Prime Minister’s confidence, but Asquith was coming out fighting and his plan could remove Lloyd George from the picture once and for all. It would also test the veracity of German calls for a negotiated end to the war. Even if Germany refused to talk, it could only play well with the Americans.

His optimism turned out to be unfounded. The following morning the Prime Minister tendered his resignation. By evening, however, the plan had backfired disastrously.

Arthur Balfour, the former Conservative Prime Minister, had been persuaded by Lloyd George to support him in return for the post of Foreign Secretary. With Balfour’s support – he had previously been loyal to Asquith – Lloyd George would be unstoppable. It also meant that Keynes would likely have a new boss. He was still struggling to digest the implications when Reginald McKenna called by.

“You look rather philosophical, given the circumstances,” Keynes said as he poured McKenna a sherry.

“All good things,” McKenna replied.

“Did he at least have the courtesy of asking for your resignation in person?”

“He did. I rather got the impression I was at the top of his list.”

“What will you do?”

“I’ll go into opposition with Asquith. Nothing else I can do.”

“Have you spoken to him?”

“No. I spoke to Margot. He’s distraught. Doesn’t want to see anyone.”

“Did he misread the situation or was he just unlucky.”

“I don’t think anyone had Balfour down for such treachery, but I do think he was taking a huge risk. I told him last week he should have sacked Lloyd George to save the government. If he’d acted then he would still be Prime Minister and I would still be Chancellor.”

“I presume Bonar Law will get your desk.”

“Yes, on his way over now.”

“Will he want me?” Keynes asked, his heart racing a little.

“That would be a risk even Lloyd George wouldn’t be prepared to take. I’m afraid you’re here for the duration.”

Thanks for reading Maynard’s War. Subscribe for free to ensure you never miss a chapter. Or take out a paid subscription and help me to deliver chapters on time.

And if you’re interested in all things Bloomsbury, and specifically 20th century British art, do check out Victoria K. Walker’s Beyond Bloomsbury. It’s fabulous.