Thank you for reading Maynard’s War, and welcome to my new subscribers. Chapter 22 will be published next Sunday, 11th May at 11am UK time. Do please share with anyone you think might be interested - it takes but a click.

If you’ve only just discovered Maynard’s War and would like to start at the beginning, then please click this button:

November 1916

There was no money left. Keynes had been anticipating the moment for at least two years, but it still came as a shock. Not only had the Government been paying for its own war, it had been heavily subsidising the French and Italian efforts. The allies were now entirely dependent on the willingness of American banks to lend at least two hundred million dollars every month. He was familiar enough with the American finance system to know the loans would be forthcoming in the short term, but the Americans would soon start wondering about repayment. And that would be impossible without an end to hostilities.

The country’s financial dependence on the United States was complicated by deteriorating political relations. The naval blockade of Germany was preventing American firms from fulfilling their contracts with German customers, with no small impact on the US economy. The government had also drawn up a blacklist of American firms who were supplying the Germans. It had all become very messy.

Keynes’ concerns were borne out when the Federal Reserve instructed American banks to reduce the credit available to foreign borrowers. This left the entire allied war financing dependent on a single Wall Street bank: J.P. Morgan. Keynes knew Morgan’s would do whatever it wanted as long as there was money to be made. The bank’s maverick founder may have been dead three years but his empire still operated as a law unto itself. It wouldn’t think twice about ignoring the instructions of its own government, but it had no special loyalty to the British either: it could pull the plug at any time.

The Somme Offensive had come to an ignominious end the previous month with a grand total of six miles gained. It had taken only a moment to calculate that the British alone had suffered one casualty for each inch of territory gained. Keynes hoped the failure of the offensive might serve to focus minds on finding a way out of the war, and he wondered if this was the reason Lord Lansdowne had asked to see him.

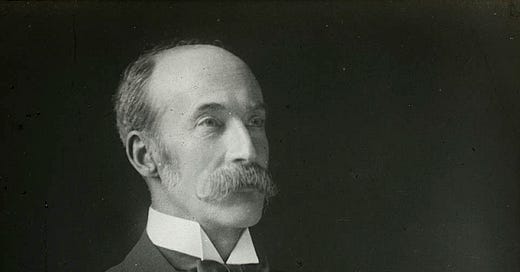

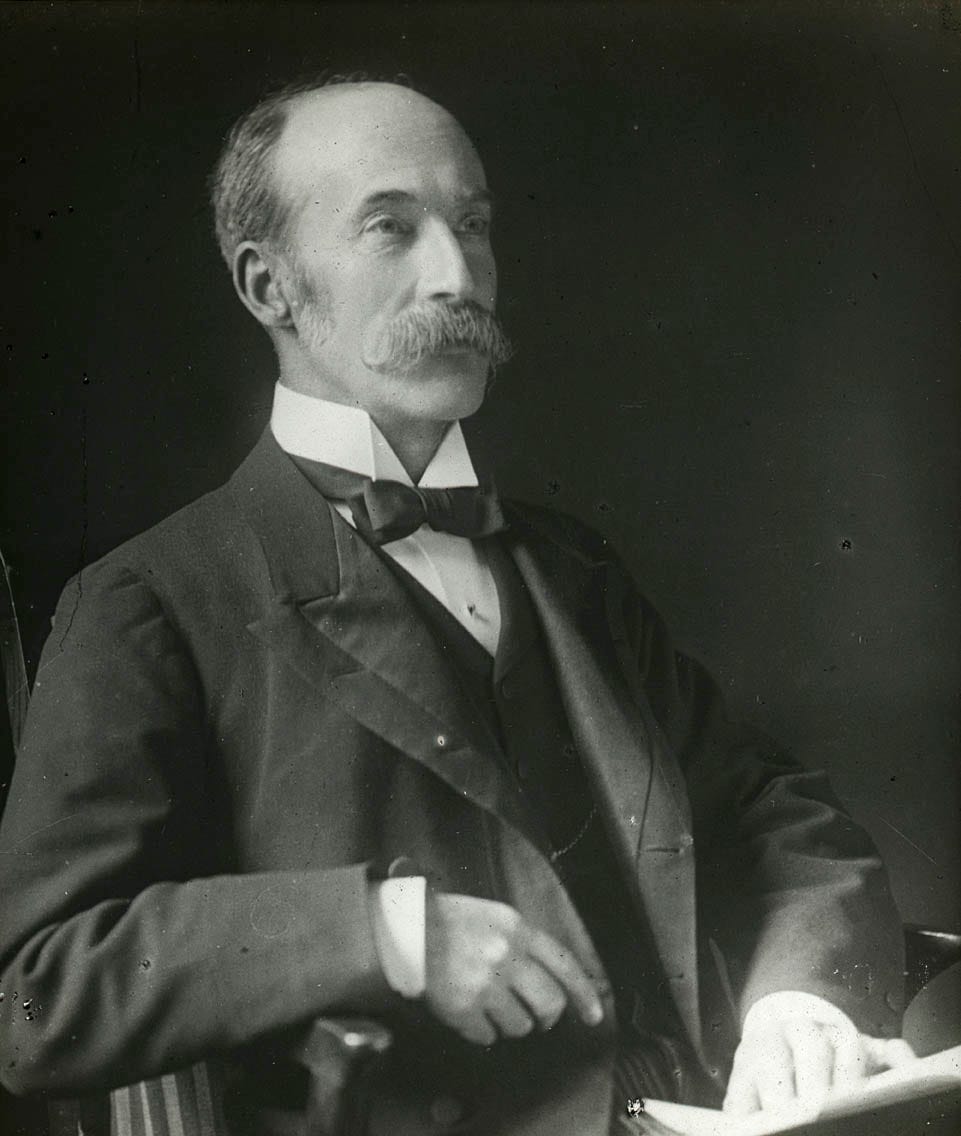

Lansdowne, a former Foreign Secretary, had an impressive reputation as a peacemaker, negotiating both the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902 and the Entente Cordiale with France two years later. His vast experience had earned him a place in Asquith’s cabinet as Minister without Portfolio. If anyone could facilitate a negotiated peace with Germany, it was he.

“Good of you to make time to see me Keynes,” Lansdowne said as he attempted to make himself comfortable in the rather hard chair in front of Keynes’ desk. “I wanted to pick your brains. People tell me you know more about the nuts and bolts of war financing than anyone else.”

“That may be true. It certainly seems to take up most of my waking hours,” Keynes answered.

“Well, I have an idea to get some movement towards a negotiated peace but I need to make sure I have my facts straight. How much longer can we continue to finance the war at current levels of spending?”

“That depends on how the long Americans continue to grant us credit.”

“Your best guess?”

“No more than three months.”

“So our lack of funds could soon force us to sue for peace, in which case a negotiated peace now might be our best option?”

Lansdowne was right: bankruptcy was the only way to force the government into negotiations, but he’d spent the last two and a half years trying to prevent this outcome. “Yes,” he answered reluctantly, “I think it would be better to sue for peace now.”

“And how are German finances?”

“The Germans continue to surprise me with their ability to fund the war. I’m not sure how they do it but we cannot assume their financial situation is worse than ours.”

“And what do you think of these noises from Germany, might they really be ready to negotiate?”

“I don’t know. But if politics in Germany is anything like politics here, there won’t be any great appetite for a negotiated settlement.”

“I think you’re right. Chancellor Bethmann-Hollweg is playing a clever game. He knows the allies will refuse his offer of talks. The war will rumble on and we shall be cast as the ones refusing to negotiate. Under these circumstances the Americans will be less likely to join the war.”

“I think your analysis is correct, but I’m not sure how it helps if your plan is to force our government into negotiations.”

Lansdowne reached into his pocket and pulled out a piece of paper which he passed to Keynes. “This is the draft of a memorandum I plan to present to cabinet next week. I’d be grateful if you’d keep it under your hat until then.”

“Yes, of course,” Keynes said, reading the memorandum. Lansdowne’s logic was unimpeachable. He argued that while the allies were unlikely to lose the war, there was little chance it could be won on the terms which any reasonable person could perceive as a victory. Better, therefore, to negotiate a peace which would enable both sides to save face. The memorandum concluded that prolongation of the war ‘will spell ruin for the civilised world, and an infinite addition to the load of human suffering which already weighs upon it.’

“If there’s anything further I can do to help, you must let me know,” Keynes said, as he handed back the document.

“Oh splendid,” Virginia said, looking up from the letter, just arrived, and handed to her by Leonard.

“Good news?” he asked.

“Yes. An invitation, from Maynard.”

“Surely we don’t need an invitation from Maynard? We just turn up. Or does his new found celebrity make us subject to a more rigorous social protocol?”

“Maynard has arranged for me to meet his friend Katherine Mansfield. You know, the young woman I told you about, the New Zealander, writes interesting short stories.”

“I see. And had you asked him to arrange such a meeting?”

“Not exactly, but she has been pestering him to arrange a meeting with me. This way I get to meet her, something I’ve been longing to do, without anyone, apart from Maynard, having the impression that I was the one doing the pursuing.” Virginia put the letter down, clapped her hands and laughed. “It’s all worked out perfectly,” she said.

“And why the fascination with Miss Mansfield?”

“As I said, she writes interestingly. Not just interestingly but differently. There is something experimental about her writing; as if she’s not satisfied with what’s gone before and wants to stir things up a bit.”

“You recognise in her a kindred spirit perhaps?”

“I wouldn’t go that far Leonard. But I am interested in her motivation, and what drives her to write with such originality.”

“Sounds like a kindred spirit to me.”

“I’m afraid you wouldn’t understand.”

He decided not to labour the point. He didn’t want to expose himself to another of Virginia’s appraisals of his own writing. He knew he was a second rate writer but didn’t need reminding of the fact as often as Virginia chose to mention it. He also knew it was her own lack of confidence that caused her to make such remarks, and while he’d never considered himself to be in competition with her, in respect of their writing or anything else, he had come to realise that she did see herself as being in competition with him. It was a characteristic he noticed in many people who achieved success in life.

He left her re-reading Keynes’ letter, still chuckling to herself, and made his way down to the basement. His publishing ambitions had suffered endless delays, not all due to the war or Virginia’s illness. The printing press had finally been delivered and put together the previous week. Until the business started to turn a profit, an unlikely prospect for at least a couple of years, money would be tight. In order to keep costs down, Leonard would have to do all the servicing and maintenance of the machine himself. He had watched it being put together with an eagle-eye, helping out whenever another pair of hands was required, and asking endless questions of the engineer. He’d been left with a detailed manual on how to operate it and today he would be producing his first practice pages. He was looking forward to getting his hands dirty.

Two hours later his hands were certainly dirty, but he had produced his first printed page, a poem of Tom Eliot’s, the type for which he had set the previous evening. As he attempted to wipe his hands on a rag already so soiled he might as well have not bothered, he sat down to admire his handiwork. There were a couple of problems caused by the type not sitting square in the tray, but apart from that, and an inevitable smudge due to his lack of a clean hand to lift the page off the machine, he was pleased with his efforts. For the first time, his dream of running a publishing house seemed like it might become a reality.

He felt he was due some good news. 1916 had been a difficult year. It had driven home just how much the war, and his wife’s illness, would change their lives. Virginia’s health had been steadily improving, and with it his feelings towards her. He would always love her, but for much of the previous year it had been difficult to imagine having a normal marriage. That was now a realistic prospect, at least it would be if the war wasn’t daily plumbing new depths in terms of bad news. Keynes remained his best source of information, but his updates were entirely negative. There seemed no prospect of a negotiated peace and he reckoned that even if the money ran out, the generals would find some way to keep the war going.

Leonard envied people who were able to get on with their lives apparently oblivious to the civilizational disaster unfolding around them. He had constantly to remind himself to focus on the things he could get on with despite the war. First and foremost, he had to earn a living. He expected Virginia’s writing to bear generous fruit at some point, and he hoped to earn more commissions for articles, but even with Virginia’s allowance, there would be little left over after paying the rent.

Neither of them liked being poor. If he could slowly build up the publishing business while generating additional revenue from small printing jobs then, perhaps, they would enjoy some security. The only alternative was politics. Since the publication of his two papers on international government he had become the subject of increasingly frequent attempts to persuade him to run for parliament. But this was not an arena in which he would excel, or even get by. He would hate the endless compromise and horse trading, and suspected he would find few people he got on with. No, he knew what he was going to do. He just wished the war would get out of the way so they could all get on with their lives.

Thanks for reading Maynard’s War. Subscribe for free to ensure you never miss a chapter. Or take out a paid subscription and help me to deliver chapters on time.

And if you’re interested in all things Bloomsbury, and specifically 20th century British art, do check out Victoria K. Walker’s Beyond Bloomsbury. It’s fabulous.