Thank you for reading Maynard’s War, and welcome to my new subscribers. Chapter 24 will be published next Sunday, 25th May at 11am UK time. Do please share with anyone you think might be interested - it takes but a click.

If you’ve only just discovered Maynard’s War and would like to start at the beginning, then please click this button:

March 1917

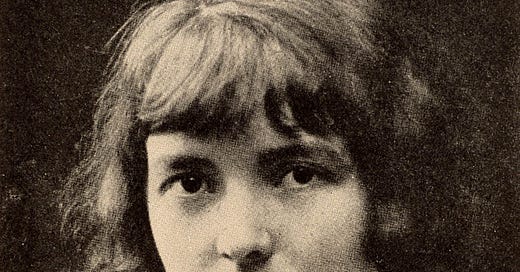

Keynes looked at his watch; it was nearly 10 o’clock. Having worked for an hour after dinner, he’d settled down to re-read the book of her own short stories that Katherine Mansfield had given him while she was lodging at Gower Street. He hadn’t seen Katherine for some time, but they had kept in touch and he’d finally managed to arrange a meeting with Virginia, who had also been impressed by Katherine’s In a German Pension.

Virginia had insisted that no formal introduction was necessary, informing him by letter that she was planning a short visit to London, she would be grateful if he could put her up, and also book a table at a small restaurant on Goodge Street which she liked, at a time to suit Miss Mansfield.

He had been delighted to find Virginia on top form when she arrived from Richmond the previous evening. They spent a pleasant evening catching up, consisting largely in Virginia quoting back at him things he had said to Vanessa or Leonard in the preceding months, then proceeding to quiz him forensically.

In most cases, he could remember neither the conversation nor the context, but he enjoyed the challenge of re-imagining why he’d said what he had apparently said, and explaining himself to Virginia’s satisfaction. He had learned many years ago that while she could be prickly, Virginia would never argue a point for the sake of it; her motive was always to learn something new. Keynes assumed this to be part of the writer’s method and welcomed her interest.

He was eager to hear about her meeting with Katherine, so when he heard the key in the door he went into the hall to welcome her back, lest she decide to go straight up to bed. Happily she marched into the sitting room and demanded a sherry. “Did you have a pleasant evening?” he enquired tentatively.

“Very enjoyable. She is an interesting woman. Interesting, but a little odd.”

This was precisely how Keynes had heard Virginia described on more than one occasion. “What did you talk about?” he asked.

“Everything really. Writing, men, the war. Yes, everything.”

“And will you see her again? Do you anticipate becoming friends?”

“Yes, I think we shall see each other again. I’m not sure we’ll become close friends. We are quite different. But I do think we are both looking for the same thing. I don’t mean wanting to be writers, rather needing to write in order to find something, something we know is there but we can’t yet articulate.”

“Something that can only emerge from the process of writing?”

“Yes, I suppose so.”

“And as a person, did you take to her?”

“She is rather coarse. I suspect she doesn’t mean to be, I think it’s just her manner. I also felt a little intimidated. Well, you know how long she’s been pursuing me. I had imagined she’d be anxious to make a good impression. Instead, it felt as if I was the one being scrutinised.”

“I think she takes her writing very seriously.”

“As we all do. I can’t imagine an unserious writer.”

“And did she talk about the man she lives with?”

“Murry, of the misspelled name? She did. It made me grateful for Leonard.”

“Not a pleasant man in my experience. I get the distinct impression his support for Katherine and her writing is intended solely to advance his own career.”

“She certainly described their relationship in very practical terms. The warmth went out of her whenever she mentioned him.”

“Did you encourage her in her writing?”

“I think we encouraged each other, in a funny sort of way. I regard her as a comrade in the struggle to commit words to paper in a way that people will find sufficiently meaningful to want to read them.”

“And how is the struggle? Your new novel, is it going well?”

“Yes, as well as can be expected.”

At breakfast the following morning Keynes received a note from Duncan: he was in London for the weekend and hoped it would be possible to meet, notwithstanding Keynes’ busy schedule. He would call at Gordon Square mid-morning on the off chance. Virginia suggested she delay her return to Richmond so they could both see Duncan who arrived shortly before noon, looking tired, and more than a little dishevelled. “Another night on the tiles?” Keynes asked, looking him up and down.

“It’s my first visit to London in months. Surely a man’s entitled to let his hair down occasionally?”

“Looks to me like you let more than you hair down.” Virginia said.

“After six months hard graft on that bloody farm, what do you expect,” he said, smiling. “I just had to escape to civilization. Sussex is lovely, but all we to do is work, and the winter is horribly claustrophobic. I hope we’ll see a little more of both of you now it’s warming up.”

“I think we can safely make promises in that respect, don’t you Virginia?”

“Yes, I really must make more of an effort with Vanessa. How’s she getting on with the house?”

“The place is transformed. She is a remarkable woman, you know. Bunny and I are very lucky to have her, organising our lives for us, keeping us out of trouble.”

“And how is Bunny?” Keynes asked.

“It’s been a little difficult to be honest. Circumstances oblige us to spend more time together than is necessarily good for a relationship.”

“Is there any aspect of the farm work that you enjoy?” Virginia asked.

“No. I hate all of it. I know it’s the only way I can avoid military service, but I want desperately for the war to end so I can have my life back.”

“And how are things going on that front, Maynard?” Virginia asked, pointedly.

“Sorry, which front?”

“The war. How much longer do we have to endure it?”

Keynes took a deep breath. “It could be over next year or it could go on for another three. It rather depends upon our friends across the Atlantic.”

“Do you really think the Americans might join the war?” Duncan asked.

“And would it make much of a difference?” Virginia added.

“I think it’s getting more likely by the day. And if they did declare war on Germany, they would, I think, commit a large number of troops. It may well be the only way to bring the war to an end.”

“And are sufficient efforts being made to persuade the Americans to join,” Duncan asked.

“I can assure you they are.”

“Splendid,” Virginia said. “Now, what shall we do? I know, how about a walk to Regent’s Park? It’s lovely outside. It’ll do us all good.” In the absence of any objection, they were soon walking north out of Gordon Square onto Taviton Street.

“I must say, Maynard,” Duncan said, it really is good of you to find some time for us. I know how busy you are at work, and you seem to have made so many new friends.”

Keynes could tell that Duncan was in the mood for mischief. “It’s true that holding a senior position in Whitehall does come with some rather onerous social obligations,” he replied.

“I knew it,” Virginia said. “Only last week Leonard was saying how much all this hobnobbing with Ambassadors and Emperors has gone to your head. But I told him that you wouldn’t be enjoying it all. Having to give up your weekends to meet the honourable someone, or his excellency whoever. I said to Leonard that you were simply duty bound.”

“It must be exhausting to have to go to all these official banquets,” Duncan continued, “but what I really want to hear about is your weekends with the Asquiths. They must be quite something. Do tell.”

“You may tease me as much as you like,” Keynes replied. “But as you know, I’ve always enjoyed company. These days I receive more invitations than I used to. The fact that many of these come from eminent people is neither here nor there.”

“Yes, but surely these eminent people are unbearably dull.” Virginia suggested.

“Some of them, yes. But most are exceptionally interesting.”

“Well, as long as you don’t disappear from our lives completely. I don’t know what we’d do without you, do you Duncan?” When Duncan didn’t answer, they both noticed he was no longer with them. Virginia eventually spotted him on the other side of the road, apparently staring into space. “Duncan what on earth are you doing,” she asked as they arrived on his side.

“Oh, hello Virginia. Sorry to abandon you, something caught my eye.”

She attempted to spot what it was that Duncan was looking at while Keynes stood with his hands on his hips, shaking his head. “I’m sorry, I’m not sure I can see anything,” she said, contorting her body in an attempt to see what Duncan could see.”

“You see the series of arches supporting that balcony on the building across the road.”

“Where we’ve just come from.” Keynes said.

“Yes, I see it,” Virginia answered.

“Do you notice anything strange about the third one from the left?”

“No, not really.”

“The stone work, inside the arch. Can you see the detail?”

“Now you mention it, it is rather ornate, and all the others are undecorated.”

“Exactly.”

“And do you have a theory as to why?”

“Duncan always has a theory,” Keynes interrupted again.

But Virginia was enjoying the game. “Go on then,” she said.

“When this building went up there were many more stonemasons at work than there are today. It was a well-respected trade, but good stonemasons were nonetheless quite common. Different stonemasons would have produced each of these arches, but I suspect arch number three was created by someone with ambitions to achieve something greater.”

“An artist.”

“Yes, and likely a frustrated one. Can you imagine the conversation when he produced that wonderful piece of work?”

“I should imagine he lost his job,” Keynes chipped in.

“Probably, but they would have had no choice but to use it or else the building would have fallen behind schedule.”

“And so our ambitious stonemason has his memorial in this impressive building.”

“Yes, although nobody knows his name, and worse still, nobody ever notices his beautiful creation.”

“Because nobody ever looks up,” Keynes explained.

“How fascinating,” Virginia murmured.

“Duncan is absolutely right,” Keynes said. Most of us hurry about our business with our eyes fixed firmly on the pavement as if we’re somehow forbidden from noticing the world around us. And I am the worst offender,” he admitted as they continued in the direction of Regent’s Park.

“You really see things don’t you Duncan, in ways that other people don’t.” Virginia said after a few moments.

“I do seem to spend more time looking at things than most people, yes. But without looking I wouldn’t see, and without seeing I wouldn’t be able to paint. Surely it’s the same with you and your writing?”

“Not really. I have to remind myself to notice things, buildings, the beauty in nature. They don’t easily attract my eye.”

“So what does?”

“People. I observe people, I listen to their conversations. I imagine what’s going on in their heads. I dissect their relationships.”

“I don’t dislike people. It’s just, well, I find they get in the way. And they spend so much time talking about themselves. People vex me, whereas things, especially beautiful or unusual things, well, they bring me pleasure.”

“And what about you Maynard?” Virginia asked, “people or buildings?”

“People in buildings,” he answered. Duncan and Virginia looked at each other, then back at Keynes. “What I mean is that I’m not so much interested in people as individuals, rather how they co-exist and work together.”

“Or fail to do so,” Virginia said.

“Exactly. Without doubt, the most important of mankind’s achievements occur when people pool their talents and work together towards a common goal. But sometimes, as we see today, the opposite happens. Human beings have the capacity to identify so strongly as members of a particular group, that periodically they band together with the sole objective of destroying other such groups with which they perceive themselves to be in competition.”

“So how do we get more people to realise that cooperation rather than competition is the way forward?”

“That, my dear Duncan, is a very good question. I have a sense it’s got a great deal to do with the economy, but I haven’t had time to work it all out yet.”

“Well you must make time,” Virginia said. “The world is waiting.”

They had arrived in Regent’s Park without really noticing. “Do you think it’s warm enough?” Keynes asked, pointing in the direction of an ice-cream seller. Virginia didn’t answer, but instead peeled off and joined the queue.

“Actually,” she said, “why don’t you queue Maynard? Duncan and I will lay claim to that bench.” She took Duncan by the arm and whisked him off.

“So, are you finding any time to paint?” she asked as they sat down.

“Not really. Too much to do on the farm, and too tired when I’m not working.”

“And how do you feel about not being able to paint?”

“Resentful. Yes, I feel resentful.”

“Towards whom, or what?”

“I suppose I resent the fact that the world is not better ordered, so I can spend my life doing what I want to do.”

“But isn’t that a little selfish. Why should you be able to spend your life doing exactly as you wish when other people can’t?”

“Oh, don’t get me wrong Virginia, I’m not claiming any special privileges. I wish the world was ordered so that everyone could spend their lives doing exactly as they wished.”

“But that’s simply not possible. Somebody has to do the unpleasant work otherwise things would grind to a halt.”

“But were it not for the war, I could be selling enough paintings to support myself. And before long you might be selling enough books to do the same.”

“I very much doubt that. Anyway, in the meantime we have to depend on our meagre inheritances, or the largesse of our parents, if they are still alive.”

“And that can’t go on forever, which is going to make it even harder for people to dedicate their lives to doing what they love.”

“Unless we turn out to be exceptionally good at what we do. And you already are, Duncan. That Spanish fellow who came to supper, the one everybody’s talking about, your work is so much more alive than his.”

“Señor Picasso? Do you really think so?”

“I’m sure of it, whatever Clive and Roger say.”

“That’s very kind of you. I really must get around to reading your novel.”

“Yes, you must.”

They sat in silence for a moment before Duncan asked: “So what brings you to town? I thought Leonard had you chained to the printing press.”

“He does, generally. But Maynard kindly arranged for me to meet his friend Katherine, so I was able to escape for the weekend.”

“How is the publishing going?”

“I think quite well. We’re not making any money yet, but I have a go on the printing machine from time to time. It’s very much a hobby for me but it’s good to have something that Leonard and I can do together. And he has a very good eye for talent.”

“And what about you Virginia? Are you well?”

“I am. But writing isn’t easy. It makes me anxious in ways that it doesn’t seem to make other writers. So then I worry that there’s something wrong with me. And before I know it, there is something wrong with me.”

“Is it other people’s opinions of your writing that cause you to worry?”

“I don’t think so. It’s more a case of not being able to express myself in the way I want to.”

“So you have a sense of what you want to say but you can’t get it down on paper?”

“I think I’m getting it down right, but when I read it back it all seems so meaningless.”

“Do you ever ask yourself why you write?”

“Yes, all the time.”

“And?”

“Well, why do you paint?”

“Because I couldn’t imagine myself not painting.”

Another silence followed before Virginia asked, “Have you seen much of Maynard, he seems a little tired?”

“Enough to know he’s working too hard. He barely gets out of London except when he’s on official business, and when he does get down to Sussex he’s usually in a dreadful mood.”

“He must be under a great deal of pressure.”

“I’m sure he is, but on his last visit, when Vanessa suggested he was taking himself too seriously, he let go a tirade of abuse. Vanessa was very upset and Maynard disappeared back up to London without any sort of apology.”

“It’s the war. It affects people, even those of us not exposed to its full horror.”

“I think it’s more than that with Maynard. He can cope with the responsibility, but you can see the conflict inside him. He’d much rather have no further involvement with the war but he can’t extricate himself for fear of what might happen if he resigned.”

“Is he really that important to the war effort?”

“I don’t know. Perhaps his sheer bloody mindedness is the only thing holding the government together.”

“Sorry for the delay,” Keynes said, returning with three ice-cream cornets. “Chap in front of me was buying for a very large family.” He sat down. “So what have you two been talking about?”

“You mainly,” Virginia said, smiling, before taking a lick of her ice-cream.

“Oh, how dull,” Keynes said.

“And how is Leonard? I heard he was up before the tribunal again,” Duncan asked Virginia.

“He was. And this time he feels most insulted. Not only did they find him unsuitable for military service, but unsuitable for work of any kind. The medical report suggested he was suffering from senile tremor. He was most put out. He’s changed his attitude to the war considerably you know? This time he was fully prepared to go to jail as a conscientious objector only to have the authorities deny him the right even to protest. And then to be diagnosed with a geriatric condition, he really was beside himself.”

“Poor Leonard,” Duncan said, laughing.

“Yes, poor Leonard. He tries so hard to do the right thing.”

“You really do love him, don’t you,” Duncan said.

“I can’t imagine loving anyone more. I am very lucky to have found him. And is my sister equally lucky to have found you?” Keynes nearly choked on his ice-cream at Virginia’s question.

“You’ll have to ask her that. Most of the time we get on perfectly well,” Duncan answered rather defensively.

“But she has to share you with Bunny.”

“It was her idea to invite Bunny to live with us.”

“But you do know why she did that?”

“Because she was able to arrange work for us both, on the farm.”

“Yes, well, I suppose that’s not untrue.”

Duncan looked confused by her answer.

Keynes sighed quietly.

Thanks for reading Maynard’s War. Subscribe for free to ensure you never miss a chapter. Or take out a paid subscription and help me to deliver chapters on time.

And if you’re interested in all things Bloomsbury, and specifically 20th century British art, do check out Victoria K. Walker’s Beyond Bloomsbury. It’s fabulous.