Thank you for your interest in Maynard’s War. I hope you enjoy this opening chapter. The second will follow tomorrow morning, Saturday 28th December, at 11am. Please do share with anyone you think might be interested. Thanks, Mark.

August 1914

Slamming the door behind him, Keynes set off in the direction of his sister’s house as quickly as he could. He was soon painfully out of breath and attracting concerned looks from the people he passed. Eyes fixed firmly on the pavement, he tried to settle into a steady pace but was already cursing his lack of fitness. He frequently resolved to take more exercise, especially since somebody had suggested sex might be more enjoyable if he didn’t find himself breathless so easily, but he was never able to find the time.

He was feeling quite sick by the time he arrived, but was relieved to find his brother-in-law working in the front garden. “Hello Maynard, everything alright? You look dreadful.” Keynes was unable to reply. “I’m afraid Margaret’s not here, she’s taken the baby to see your parents. Is it something urgent?”

“Archie, good,” he began, still struggling for breath, “no, it’s you I wanted, not Margaret.”

“Oh, I see. Well, what can I do for you old chap?”

“That motorcycle of yours, running alright is it?”

“Certainly is. Took Margaret to Ely in it yesterday. Had a lovely time.”

“Good. Listen, are you terribly busy? I simply must get to London this afternoon and the trains are no good on a Sunday.”

“What’s going on?”

“It’s to do with war.”

“Well in that case let me put these away,” Archie said, waving his garden shears uncomfortably close to Keynes’ moustache.

He leant against the gate post to compose himself. If his body was convulsing, his mind was racing. What was he to make of the note from his old friend Basil Blackett?

It was six years since he had walked out of the India Office, a decision that had not endeared him to precisely the people he needed to cultivate if his ambitions of a career in the upper echelons of the civil service were to be realised.

But it had been the right thing to do: he’d built an enviable academic reputation in the meantime, and dividing his life between Cambridge and London allowed him to remain in close touch with friends from his time as an undergraduate. Besides, following a conventional civil service career path would have been unbearably dull.

Nonetheless, for some time he’d been hoping for an opportunity to return to the centre of things. Perhaps now, with the Government embroiled in a crisis to end all crises and the country on the brink of war, somebody in Whitehall had finally decided to seek his advice.

Since their time together in the India Office, Blackett had moved to the Treasury, winning the trust of the Chancellor, David Lloyd George, an achievement few could claim. His note had given little away: ‘My Dear Keynes, Your immediate attendance at HM Treasury might prove beneficial to all parties. Best Regards’. He wished he’d given more attention to the international financial situation in recent weeks. Mind you, he was probably better informed than most so-called Treasury experts, and it wouldn’t take long for Blackett to bring him up to speed.

The sound of heavy bolts dragging on the driveway as Archie pushed open the garage doors was followed by a throaty roar from the engine of his motorcycle. As he turned to look, Keynes saw the khaki-coloured contraption lurch towards him. Archie handed him a ribbed leather helmet and a pair of goggles retrieved from the floor of the sidecar.

“Margaret has kindly left you her cushions from yesterday, so you shouldn’t be too uncomfortable,” he said. “You’d better hold on though, if we’re going to have you in London for tea I’m going to have to push pretty hard.”

Keynes sunk down into the seat of the sidecar and was still fumbling with the unfamiliar motoring attire when Archie kicked the machine into gear. He had ridden pillion with him on a couple of occasions around Cambridge. It was an arrangement he’d found rather pleasant, though loyalty to his sister obliged him not to allow that particular fantasy to develop any further. But he found the sidecar to be quite a different matter: not the ideal mode of transport, he suspected, for one who bruised as easily as he did. It reminded him of the time when, as an undergraduate, and much the worse for drink, he’d unintentionally made the entire journey from Kings Cross to Cambridge in a third class carriage. At least on that occasion he’d had the benefit of being barely conscious.

Within minutes they had escaped Cambridge and were tearing along open country roads. Keynes found that if he allowed himself to roll with the movement of the vehicle, he was much more comfortable. He was impressed at the speed of Archie’s machine, especially on long straight sections of road.

It was soon after the end of one of these that his putative contribution to the war effort almost came to an end. As Archie turned into a blind bend the road narrowed and they were greeted by the sight of a large truck not twenty yards ahead of them. Neither vehicle had any hope of stopping but both drivers made skilful use of the grass verge, so avoiding a collision. Keynes had to duck down in the sidecar to avoid brambles protruding from the hedge, and at one point thought he might be hurled out, but Archie succeeded in returning them safely to the road.

Keynes looked back towards the truck. It was open at the back, its cargo a platoon of uniformed soldiers. Something he had never seen before.

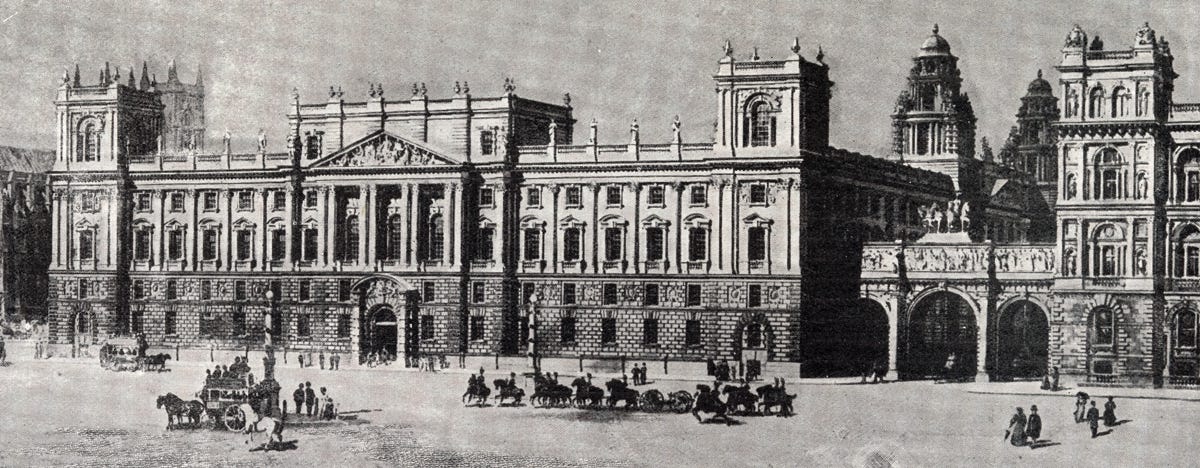

The roads between Cambridge and London had been as quiet as one would expect on a sunny Sunday afternoon. As they thundered along The Strand, Keynes was becoming excited. Returning to London was always a thrill but this was surely the most thrilling return he had made. By the time they reached Whitehall, he had removed his helmet and goggles. As they turned into King Charles Street, Archie momentarily forgot about the sidecar and Keynes thought his life would end dashed against the substantial pillars supporting Brydon’s magnificent triple arch, the construction of which he had admired from his window during his final year at the India Office. But Archie adjusted in the nick of time and seconds later screeched to a halt outside the entrance to the Treasury. Keynes leapt onto the pavement, tossing his helmet and goggles back into the sidecar. He thanked his brother-in-law profusely before running inside.

As he presented himself at the small hatch inside the grand revolving door, Keynes remembered that although invited, he wasn’t really expected. He explained to the doorman that Basil Blackett had summoned him on a matter of the utmost importance. The man seemed unimpressed. It occurred to Keynes that with things as they were, everybody’s business was likely to be of the ‘utmost importance’.

“If you’d like to take a seat, Sir, I’ll telephone up to Mr Blackett and let him know you’re here,” the man said, patiently.

The only chairs were situated on the far side of the cavernous lobby, so he made his way over as instructed. He’d only been seated a few seconds when Blackett came hurtling down the stairs. “Maynard,” he shouted, “how marvellous to see you. I must say I wasn’t expecting you until morning. Were you in London?”

“No, no. Just arrived from Cambridge, by motorcycle in fact. I thought I’d better make a special effort. I took your message to mean that things were pretty serious?”

“Serious doesn’t begin to describe the mess we’re in. I think it best if we take a walk. I can’t get a minute to myself upstairs and I think we should keep you out of sight, at least until we have a strategy for getting you into a position from which you can start banging some heads together.”

As they made their way on to Horse Guards Parade and Keynes caught site of the trees in St James’s Park, he felt a wave of elation. London was lovely at this time of year, and he was exactly where he wanted to be. “Let me see if I’ve got things right,” he began. “Banks not getting their foreign loans repaid because of the fear of war?”

“Correct.”

“350 million outstanding at close of play on Friday, give or take?”

Blackett gave him the kind of look one gives a child suspected of cheating: “Exactly 350 million,” he said.

“I was hoping it would be less. Things are pretty bad then?”

“That’s why I thought I’d better get you down here.”

“So the banks are facing insolvency, at least they think they are, and Friday was the last day of the month. Foreign investors can’t settle their accounts with the stockbrokers, so the stockbrokers can’t repay their short-term loans and are having to resort to selling shares, causing the markets to plummet.”

“Exactly. It’s a vicious circle. We had to close the stock exchange at lunchtime on Friday.”

“And presumably it won’t open in the morning?”

“Not until Thursday at the earliest. Three day bank holiday as well.”

“Good. Presumably the banks are running cap in hand to the government, saying things can’t possibly go on like this, pleading poverty and hysterical at the collapse in the price of their own shares?”

“Right again, they’ve asked Lloyd George if they might be temporarily relieved of their obligation to convert to gold.”

“Spineless bastards!” Blackett smiled at Keynes’ reaction. “How do they think they can be temporarily relieved of that obligation. Come off the gold standard and we’re off for good. What have you done with the bank rate?”

“Up to ten per cent.”

“Understandable in the circumstances, but it won’t help if the Chancellor lets the banks off the hook. How are the gold reserves?”

“Twelve million gone.”

“Just under half.” Keynes stroked his moustache and took a deep breath. “What did Lloyd George say to the banks?”

“He said he’d think about it over the weekend.”

“God save us from politicians. If the markets even suspect the government is going allow the banks not to fulfil requests to convert to gold, confidence in London will disappear in an instant.”

“Yes.”

“And the timing would be disastrous, the most severe financial crisis in a century in the week we declare war. What is Lloyd George thinking?”

“I’m afraid he doesn’t understand how the system works. The bankers have threatened financial armageddon if he doesn’t protect them and nobody is offering any other way out.”

“I imagine you’ve tried.”

“Of course, but Paish won’t let me though the door.”

“If he won’t let you anywhere near, what chance do I have?”

“I was thinking a memorandum. He doesn’t even have to know you’re in London.”

“I see.” Keynes took a deep breath. “I’ll need a desk, and of course I’ll need all the papers, whatever figures you have to hand. And a telephone. And don’t you go disappearing on me, Basil.”

“Do you think we can save the situation?”

“That depends on whether Lloyd George is as stubborn as his reputation suggests. If we don’t sort things out this week it could takes months for proper levels of liquidity to return to the markets. If we can’t persuade the Chancellor to change course, and quickly, then we might as well plant a sign at the entrance to Dover harbour welcoming the bloody Kaiser.”

Keynes was alone in the tiny room in the India Office commandeered by Blackett so they might work without anyone at the Treasury getting wind of the fact he was in London. The memorandum had been reasonably straightforward. A few phone calls to the city to confirm, and in several cases to revise, the figures given to the Treasury by the banks, and he had everything he needed.

The financial mechanics of the situation were reasonably simple, and he was sufficiently well-versed in the factors that influence market sentiment to know his solution would be effective. But how to persuade a Chancellor who understood neither and was notoriously reluctant to take advice? Keynes would have to give him something. Lloyd George clearly felt some obligation to the banks who were holding the country to ransom. He’d have to give them something too, and that was the tricky part.

In the end he settled on a classic compromise, a deal that, in the Chancellor’s ignorance, and the bankers stupidity, would persuade them both they had won the day while preventing them from bringing the economy to its knees. Once he had the strategy worked out, it was then simply a matter of giving Lloyd George the confidence to take ownership of the plan and impose it on the banks without further discussion.

He and Blackett had spent the entire morning drafting and re-drafting the memorandum. Blackett had been happy with it at eleven. It had taken a further three drafts for Keynes to convince himself that it was safe to send his friend scuttling off to the Treasury to deliver the document. That was three hours ago, and still no word.

Blackett had thought it unlikely he’d be able to deliver the memorandum in person, which meant it would have to cross the desk of Sir George Paish. Keynes knew that Paish disliked him. The only reaction Paish provoked in Keynes was pity, for a man who had been promoted beyond his level of competence. He shuddered to think that this man was advising the Chancellor on international finance.

It was entirely possible that the memorandum would get no further than Paish’s desk. With this in mind, Keynes had drafted the paper in the simplest possible terms. He would need to persuade Paish of his case, in order for Paish to take it to Lloyd George.

He was also aware that Blackett was delivering a job application on his behalf. If Lloyd George was sufficiently impressed, then this sojourn in London might turn into a permanent appointment, or at least one for the duration of the war. With so much riding on the outcome, for Keynes personally and for the country, he found himself uncharacteristically nervous.

There was a loud thump on the door and in bounded Blackett with a huge smile on his face. “Remind me to invite you next time there’s a game of poker,” Keynes said as he rose to greet him. “Good news, I take it?”

“So far, so good. I was sat outside Paish’s room for two hours. He had the memorandum himself for the first hour. Then he came out and hurried down the corridor, in the opposite direction from Lloyd George’s office. He must have used the back stairs because I didn’t see him again until his secretary invited me in and there he was, sat behind his enormous desk, trying to look important.”

“And what did he say?”

“Mr Lloyd George asks that you thank Mr Keynes for his memorandum which he found most helpful.”

“Is that all?”

“Yes, that’s all.”

“So what do you think?”

“I think he’ll do everything you suggest.”

“And will it do me any good?”

“Too early to say, but it’ll certainly do the country some good.”

Thanks for reading Maynard’s War. Subscribe for free to ensure you never miss a chapter. Or take out a paid subscription to help me to deliver chapters on time.

And if you’re interested in all things Bloomsbury, and specifically 20th century British art, then check out Victoria K. Walker’s Beyond Bloomsbury. It’s fabulous.