Thank you for reading Maynard’s War. I hope you enjoy this second chapter. The third will follow tomorrow morning, Sunday 29th December, at 11am. Please do share with anyone you think might be interested. Thanks, Mark.

August 1914

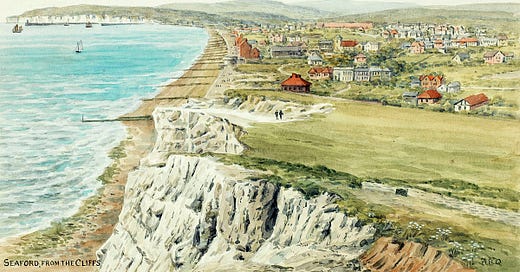

Leonard Woolf couldn’t remember a summer like it - simply glorious. How lucky they were to have a home so close to the coast. Every year it was a delight to be here, but this year he’d been able to bathe whenever he wished. It was a short bicycle ride to the long, empty beach at Seaford. He was surprised how few people took advantage of the warm days; perhaps nobody shared his passion for sea swimming, but it was the place he felt most at home. It was also the only time he was free of the dreadful tremor in his hands that had tormented him all his adult life.

As he swam towards the end of the groyne at the eastern entrance to Newhaven harbour he reflected on the cause of this physical curse. The tremor was not sufficient to prevent him from doing anything practical. He could write without difficulty, he could tend the garden and he could carry cups of tea to his wife, wherever she happened to be working. In fact, the tremor was at its most ferocious when he wasn’t doing anything with his hands, and that’s when people noticed. Those who didn’t know him mostly concluded he had a drink problem. He hated being judged in this way but rarely got the chance to defend the accusation.

People who knew him better, but not well enough to have heard his attempts to explain the affliction, assumed he suffered from some kind of anxious condition, or was so shy that the prospect of meeting people caused him to shake uncontrollably. Neither of these was true. He wasn’t the most gregarious of individuals, and he’d always enjoyed his own company, but meeting people didn’t make him anxious, although it often left him bored.

He’d been fortunate during his time at Cambridge to have met some of the most engaging, interesting and accomplished people in the country. In terms of stimulating company, he suspected the zenith had been reached rather too early in life. He no longer saw the need, as so many of his contemporaries apparently did, to endlessly add to the roster of people with whom he might socialise. His wife was the polar opposite, at least when she was well. At the moment, though, she was unable to see anyone.

Arriving at the groyne, he heaved himself out of the water and lay down on the warm concrete. He would rest for ten minutes before making the return journey. He noticed how the cool water had lowered his body temperature and wondered if this was the cause of his tremor reducing while swimming. He frequently set himself observational tasks that might facilitate a diagnosis of his condition, but invariably his mind wandered on to something more interesting. He hoped that medical science would catch up with him before he was too old to enjoy the cure.

As he lay in the warming sun, his thoughts were once again taken over by concern for his wife. She had been unwell for several weeks, and while the current episode didn’t yet qualify as a full-blown breakdown, it was getting perilously close. Apart from the obvious difficulty of living with someone suffering from a serious emotional illness, he was unable to invite anyone to the house, nor could he leave her for more than a few hours; a trip to London was out of the question. He had been fully aware of her history when he’d married her, but he sometimes wondered if he’d bitten off more than he could chew.

Reckoning his ten minutes were up, he stood up and dived into the clear blue water below. With the tide coming in, fifteen minutes at a brisk pace should have him back on the beach at the place where he’d left his clothes.

Approaching the shore he became aware of a number of other bathers; the warm weather had clearly driven a number of non-regulars into the water. Not yet ready to acknowledge the existence of other human beings, he sunk beneath the gentle waves and swam underwater before surfacing once he was in his depth. As he rubbed the sea water from his eyes and the world came back into focus, he was confronted by a ruddy-faced man with an impressively waxed handlebar moustache.

“I’m so sorry,” Leonard offered, “I hadn’t realised we were so close.”

“Don’t worry,” the man replied, “least of our problems now, don’t you think?”

“I don’t quite follow,” Leonard said.

“Haven’t you heard man? We’ve just declared war on Germany.”

Returning to the beach, he lay back on his towel and let the sun dry him. He was strangely unmoved by the news; war had seemed inevitable for some time.

As he fastened his wristwatch he realised he’d been out too long, and while he knew the nurse would wait, when she wasn’t well, Virginia had a tendency to become irrational. He’d promised her he would be home by five. If he wasn’t she would likely consider herself abandoned. When, several weeks ago, he’d been unavoidably delayed on his return from London, she’d had to put herself to bed. He was pretty sure the overdose she’d taken on that occasion had been accidental, but he couldn’t be certain. In any case, it was that episode that had triggered the current crisis.

He used one of his socks to clean the sand from between his toes before putting on his clothes and returning to his bicycle. The ride back to Asheham was the harder of the two legs, but he relished the exercise.

Turning off the main road into the overgrown lane that led to the house, Leonard immediately saw the window of Virginia’s bedroom flung wide open and her bedding hanging out to air. This could mean only one thing: not only was his wife up and about, she must also be feeling better, or she wouldn’t have allowed the nurse anywhere near her bed. Leonard felt an enormous weight lift from his shoulders.

And there she was, sitting on the veranda, reading. He approached her with a bounce in his step and was delighted as she got up to greet him.

“There you are, my love,” she said. “I just said to Fanny that if you weren’t back by the time I finished this,” she waved the book in the air, “then we would have to send out a search party.” She threw both arms around him and held on for so long that Leonard wondered if she hadn’t returned to reading her book over his shoulder. “There,” she continued, apparently pleased with herself for having successfully completed a task she couldn’t have contemplated at any time in the last fortnight. She looked at Leonard with the same unaffected smile that had first made him fall in love with her.

“How was your afternoon?” she asked, pulling the other veranda chair close to hers, so he could sit beside her.

“It was lovely, thank you. The sea was clear as crystal.”

“Did you swim a long way?”

“I did, although I was brought up short on my return to the shore.”

“Why, what happened?”

“I literally swam into a chap in the shallows, and as I tried to apologise he told me the news.”

“About the war?”

“Oh, so you know?”

“Yes, Fanny’s daughter came by. She was rather upset, wanted to talk to her mother.”

“And Fanny told you?”

“Yes, well I heard the poor girl sobbing in the kitchen. I wondered what could have happened. So once she was gone I asked Fanny, and she told me.”

“And what do you think?”

“I really don’t know what to think. I can’t imagine our being at war, can you? It’s something I thought we’d grown out of, as a country I mean.”

“If only that were true.”

“I must be incredibly selfish. The first thing that crossed my mind was whether we would still be able to go to Scotland. I was so looking forward to the holiday.”

“I have to admit it did cross my mind too.”

“So, can we still go? Oh, Leonard please, say yes.”

Whenever Virginia sensed she might not get her way, she would beg like a child. Leonard found it at once endearing and irritating. “I can think of no reason why we shouldn’t keep our plans to visit Scotland. I’ve no idea how the war will unfold, but the Germans are not going to reach the channel before Christmas, and Hadrian’s Wall will take them a deal longer,” he answered.

“Are you sure?”

“Yes. Nothing much will happen in the next few weeks. And by the time we return things should be clearer. We’ll have more of an idea what impact it’ll have on our lives. Then we can make plans for the future having had a good rest. In any case, had you forgotten that Maynard is taking the house at the end of August?”

“Oh yes, and he’ll doubtless be counting on our absence so he can do his entertaining.”

“Don’t be wicked. He pays us a very good rent, and he’s entitled to do as he pleases when he’s here.”

“I make no judgment. But you’re right, it would be much better if we were to make ourselves scarce. That’s decided then: three weeks in bonnie Scotland. I am so looking forward to it.” As she finished, she noticed that Leonard was no longer listening to her. “Have you left me?” she asked.

“Sorry, I was thinking about the war.”

“You don’t think you’ll have to fight, do you?”

“I’m not sure I’d make much of a soldier.”

“You’re too old, surely?”

“I’m only thirty-four.”

“Yes, but you couldn’t possibly fight.”

“I know. Look at the trouble I had pulling out those dead foxgloves yesterday.”

“Yes. I don’t think we need worry. Whatever examinations they give you, you’re bound to fail. In any case, aren’t we supposed to be pacifists?”

“I’m not sure one can be confirmed in one’s pacifism until tested in the face of a real war.”

Thanks for reading Maynard’s War. Subscribe for free to ensure you never miss a chapter. Or take out a paid subscription to help me to deliver chapters on time.

And if you’re interested in all things Bloomsbury, and specifically 20th century British art, do check out Victoria K. Walker’s Beyond Bloomsbury. It’s fabulous.