Thank you for reading Maynard’s War. I hope you enjoy this third chapter. Chapter 4 will follow next Sunday morning, 5th January, at 11am. Please do share with anyone you think might be interested. Happy New Year!

September 1914

It had taken Keynes several weeks to get over the disappointment. Just when it seemed he had worked his way into a position at the heart of government, word had come from Basil Blackett that his appointment had been blocked.

George Paish had felt threatened by the facility with which his memorandum had persuaded Lloyd George to change tack, and the Chancellor had taken little persuading that with the immediate crisis having passed, there was no need to bring another adviser on board. He wouldn’t have felt so hard done by had Lloyd George not proceeded to take all the credit for the strategy. They hadn’t even offered to pay him for his time.

Blackett’s advice was to sit tight. Paish told Lloyd George what he wanted to hear, but neither man had a grip on the intricacies of international finance. It wouldn’t be long until the next crisis, and Paish wouldn’t be given another chance.

Keynes had returned to a Cambridge already denuded of its best students, and what teaching he had been called upon to do had left him singularly uninspired. To top it all, none of his friends had invited him to London for several weeks. While in normal times he wouldn’t have thought twice about pitching up unannounced, everybody had been knocked off kilter by the war; friendships he had previously taken for granted now seemed uncertain. At least he had lunch with his parents to look forward to, and Margaret and Archie would be there.

As he made his way through Cambridge he was aware of the changed atmosphere of the place. This great centre of wisdom and learning had effectively stopped functioning because of the war; the lessons of history deliberately ignored; the irony apparently lost on everyone.

He was interested in his own reaction to the war. It was, of course, a terrible thing. Many lives had already been lost, and the suffering extended beyond those who had fallen, to their loved ones.

At an intellectual level, however, he found the whole thing quite fascinating. He chuckled to himself as he imagined his pacifist-minded friends berating him for taking such a rational view. He wondered why he was able to be so dispassionate about it, then he wondered why other people were not. It occurred to him that he had no real experience of suffering, and that perhaps suffering was a precondition for empathy. Certainly he’d had one or two disappointments in his life, notably in respect of romantic involvements which invariably ended at the behest of the other party. But on each occasion he had quickly recovered. Such episodes were simply part of life and in no way comparable to the suffering endured by those who lost their loved ones to the war.

Too bad if his friends found his attitude discomfiting; he saw the war as an opportunity, and not simply in terms of his own ambitions. Problems were there to be solved. The bigger the problem, the greater the challenge. His was the kind of mind that needed such challenges, and practical challenges were so much better than theoretical ones; if successfully overcome they could have a real impact on people’s lives. It was in this sense that the war presented an opportunity, and why he was so frustrated to be denied proper involvement.

He was pleased to discover that Margaret and Archie had left his niece at home with the nanny. Not that he didn’t like children, but he hadn’t seen enough of his sister or her husband since the birth and was looking forward to some adult conversation with people whose company he enjoyed.

He appreciated his good fortune in respect of his parents. He’d lost count of the times acquaintances had reminded him of the adage about not getting to choose one’s parents, which they invariably used to preface a depressing tale of strained relations, and in some cases, no relations at all. Chief among these accounts was that of Clive Bell. The behaviour of Bell’s father, a very successful man by all accounts, was beyond understanding. It was so bad that each time Clive and Vanessa were obliged to make the trip to Wiltshire, Keynes found himself unable to relax until he’d received news of their safe return to London.

It was through the experiences of others that he had come to understand that his relationship with his parents was not just untypical but possibly unique: his mother and father were among his closest friends and had been for as long as he could remember. They’d always encouraged and supported him in everything. The only time he could remember being admonished by his father was when he’d been unkind to visiting friends who had struggled to keep up with the conversation. “You must remember, Maynard,” his father had said, “not everyone is blessed with a mind like yours. You must take this into account during conversations or people will think you arrogant.”

“But mother is always saying that you have no time for fools,” he had answered.

“Even fools can be useful sometimes,” came the reply, “and it doesn’t do to be rude to people, especially people who are guests in our house.”

Thankfully there were no fools present today. Only his delightful sister, her immensely clever husband, whom he’d already marked down as future Nobel laureate, and his adored parents. “So, Maynard, have you got over your disappointment?” Archie asked, as they sat down to lunch.

“I’m coming to terms with it,” he said, determined to appear upbeat. “There’s nothing I could have done differently. I am simply a victim of political circumstance.”

“And might another such opportunity come your way?” his father asked.

“Basil Blackett thinks Lloyd George is too clever not ultimately to realise he’s being badly advised.”

“And is there anyone else he might turn to?” Archie asked, “apart from you, I mean.”

“Not really. International finance has changed beyond recognition these last few years. Most of the older generation did their learning at a time when the world was far less complex. They also seem to have a difficult relationship with the idea of change.”

“And among the younger generation?” enquired Margaret.

“Again, no. They specialise too early. Nobody understands the need to see the bigger picture.”

“So if Lloyd George is the politician people think he is, he will eventually turn to you,” his father suggested.

“He might. But I’m not sure anyone really knows what makes Lloyd George tick.”

“And in the meantime,” his mother asked, “are you finding plenty to keep you occupied here in Cambridge?”

“Not really. You can see for yourself how few students there are this term. I have rather too much free time.”

“I have just the thing for you,” Margaret said. “The military hospital, they’re in desperate need of volunteers.”

“I can’t really see myself as a nurse,” he spluttered.

“No, no. They’re short of men to do the heavier work: moving beds, disposing of soiled dressings, taking in supplies, that sort of thing. They also need people who are happy just to sit and talk to the patients. Some of them have long term injuries and will be here for weeks. Their families are all over the country so they don’t get visitors. The nurses are too busy to spend time bolstering patient moral.”

“I suppose that does sound interesting,” Keynes replied. “My knowledge of the war comes either from the newspapers, most of which have little idea what’s going on, or from politicians and civil servants who appear to have none at all. It’ll do me good to get a different perspective.”

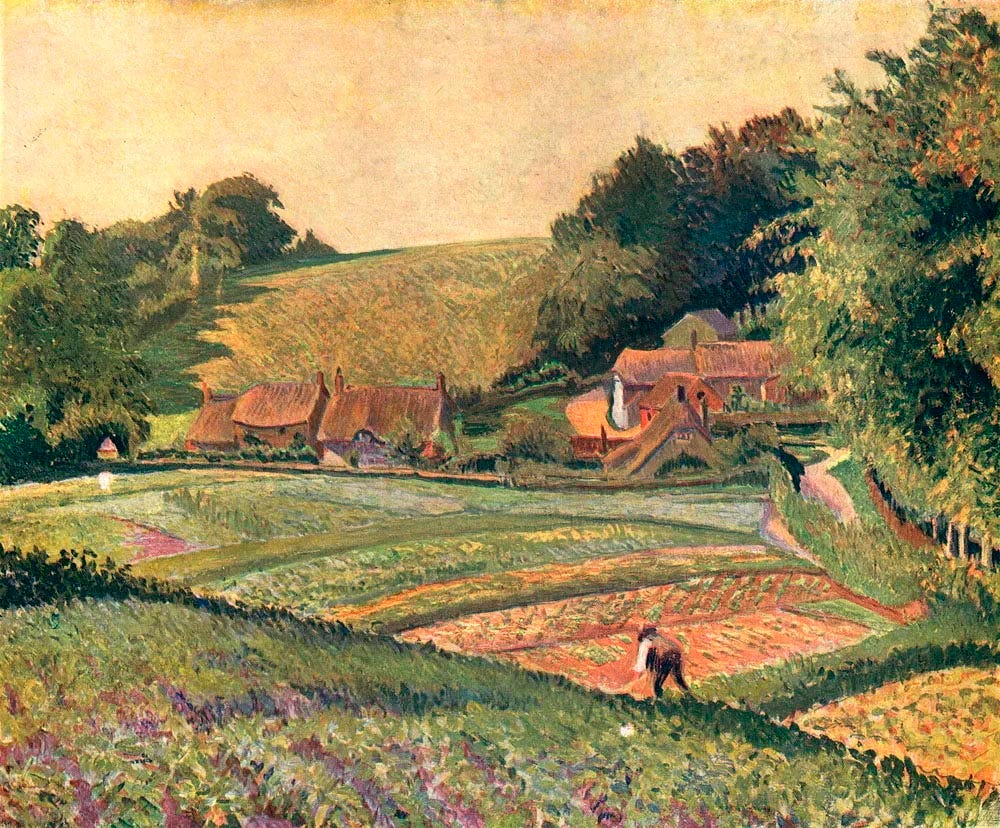

The unspoilt view across the rolling Wiltshire countryside did nothing to lift Vanessa’s spirits. Neither could the warm sun persuade her that the world was anything but a horrid, cold place. She corrected herself: there’s nothing wrong with the world, she thought, it was the people in it, especially people like Clive’s father. He was the worst kind of bully: controlling people by keeping them firmly in sight and cutting them down the moment they dared express an opinion of their own. In the early days of their marriage, Vanessa had been allowed a little more conversational liberty, but after eight years she was now treated with the same disdain that Clive’s father reserved for the rest of the family.

Despite her best efforts to tolerate him, today she had managed to survive only ten minutes beyond lunch. Unusually among the successful middle classes, who took every opportunity to ape the aristocracy, Clive’s father didn’t dispatch female company to the drawing room after a meal. Vanessa suspected he didn’t dare leave his wife and daughter-in-law together for fear of what they might discuss. Clive was still stuck inside, but only for his mother’s sake. He would join her on the veranda soon enough.

These fraught visits to Clive’s parents were, however, the only time she felt properly married to her husband. He was immensely grateful for her support in respect of his father, but it was the only part of their marriage that remained constant. She would never forgive Clive for destroying the life she had dreamed of. If it hadn’t been for the children, she would certainly have left him. At least his insistence on what he called an ‘open’ marriage had enabled her to pursue a relationship with Roger Fry without guilt, but even her feelings for Roger were now changing in a way she didn’t entirely understand.

She and Clive had both been vehemently opposed to the war since it began. She was determined not to become depressed about it, but now, having been on the receiving end of another tirade of jingoistic nonsense from her father-in-law, thought of the war made her utterly miserable. Thousands of men on both sides had already been slaughtered, but to listen to Clive’s father you’d think the war was the best thing that could have happened: young men would be given a proper focus. People would once again learn a sense of patriotism and duty. And in any case, war was the human equivalent of a deer cull; the species needed thinning out every generation or so.

But best of all, it would give the economy just the boost it needed. At this point Vanessa had enquired whether the Bell coal business had enjoyed an improvement in its fortunes since the outbreak of war. Clive’s father replied that orders were up fifty per cent and he was planning to acquire an estate in Scotland with the proceeds. Vanessa looked at her husband; it was little consolation to see her contempt reflected in his expression. At the beginning of their relationship she had wished he would tackle his father’s ignorance and pomposity, but over the years she’d learned there was little point.

She heard Clive’s footsteps on the stones behind her. He put his arms around her waist and rested his chin on her shoulder “I’m sorry darling,” he said, softly.

“You don’t need to apologise,” she said. “It would be easier to take if he wasn’t expressing opinions held by millions of people up and down the country.”

“How would they know any differently?” he shrugged. “They just rehearse what they read in the newspapers. Nobody’s offering an alternative point of view.”

“At least you’re trying.”

“Yes, but I had another rejection yesterday, from The Nation this time.”

“And it calls itself a liberal journal.”

“I think I might change tack, stop firing off articles and write a pamphlet instead.”

“But will you have any more success finding a publisher for a pamphlet?”

“We can publish it ourselves.”

“And what will you say?”

“The war is already proving disastrous. It could go on for years and cost hundreds of thousands of lives on both sides. It could and should have been avoided, and priority must now be given to pursuing a negotiated settlement with the Germans.” He looked at her and saw her smiling. “Oh dear, should I get off my soapbox?”

“Not at all. I love your passion.”

“That’s all very well, but will you buy a copy?”

“I’ll buy a hundred and distribute them to everyone we know who supports the war.”

“Including Maynard?”

“I might just hit Maynard over the head with the box. His problem is that he’s too clever with words. Even if he opposed the war with all his heart, he’d still argue in its support, just to make a point.”

“We must get him over to our side. If he does secure this government post he might be able to bring some influence to bear.”

“But even if we do, even if he can, ours is such a minority view, will the government feel under any obligation to listen?” Vanessa sighed.

“If only politicians had the courage to lead opinion, especially on the big moral questions, instead of simply following the herd and kowtowing to the press, things might be different.”

“It wouldn’t surprise me if a majority of members of parliament share your father’s views.”

“You’re probably right. But for now, if you can bear it, there’s coffee and petits fours in the library. I’ll do my best to steer conversation away from the war.”

“Petits fours! Whatever next?”

Thanks for reading Maynard’s War. Subscribe for free to ensure you never miss a chapter. Or take out a paid subscription to help me to deliver chapters on time.

And if you’re interested in all things Bloomsbury, and specifically 20th century British art, do check out Victoria K. Walker’s Beyond Bloomsbury. It’s fabulous.