Thanks for reading Maynard’s War, and a warm welcome to my new subscribers. Chapter 20 will be published next Sunday, 27th April at 11am UK time. Do please share with anyone you think might be interested - it takes but a click.

If you’ve only just discovered Maynard’s War and would like to start at the beginning, then please click this button:

September 1916

It had been the most awful summer. Had Keynes not seen the official reports for himself he wouldn’t have believed the casualty figures. The Somme offensive was supposed to mark the beginning of the end of the war. Instead it had become the greatest blood bath in history. And still the generals were set on continuing with a futile strategy. Asquith was deeply uneasy but he couldn’t call off the offensive without a tangible victory. Everything Keynes believed would follow from an escalation of activities on the western front had come to pass, only with casualties far in excess of those even he had feared.

Needless to say, the mounting casualty figures also had a financial cost. Keynes hated having literally to put a value on human lives, but still felt he had no option but to continue in post; Asquith and McKenna needed him more than ever. As he wondered how much worse things could get, his secretary came in looking flustered. “Mr Keynes, the Prime Minister has asked to see you, at once,” she said.

“I see.” Keynes was surprised. He rarely met with Asquith in Whitehall, and never had a private audience. He stood up. “I’d better pop round to No. 10 then, I suppose. Don’t worry,” he said, noticing the concern on the woman’s face, “I’ve no idea what he wants, but I’m pretty sure it won’t be my head on a plate.” She smiled and passed him his coat and hat.

“Keynes. Good. Do come in,” Asquith said as he was shown into the Prime Minister’s study. “I just wanted to thank you for this.” He held up a report that Keynes had prepared for Cabinet. It contained nothing unusual or particularly original; he still had no idea why he’d been summoned. “Fine work. I’m very grateful for your continued efforts and your loyalty. I’m told you are the hardest working civil servant in Whitehall. I really am very grateful.” Keynes thought it was starting to sound ominous. He waited for a moment, expecting Asquith to say more, but instead the Prime Minister seemed at a loss for words. Eventually he spoke: “How old are you Keynes?”

“I’m thirty-three, Sir.”

“Ah yes, a little younger than Raymond,” Asquith said, under his breath.

“I’m sorry Prime Minister, I didn’t quite catch that.”

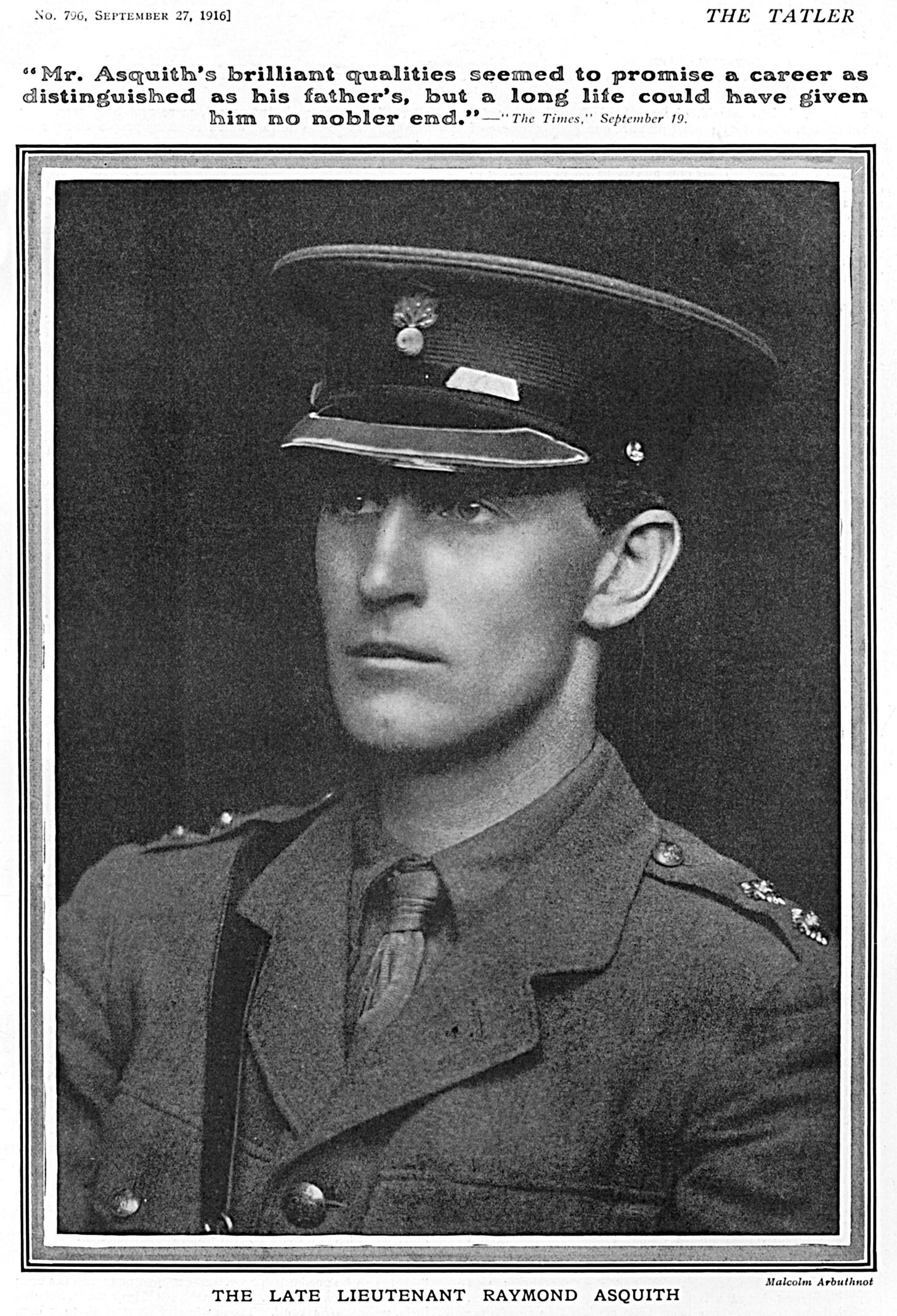

“You’re a little younger, than my son, Raymond. He was thirty-seven,” Asquith answered. He took a deep breath and his head fell into his hands.

“Prime Minister, I am so sorry. I didn’t know Raymond had been killed. When did you find out?”

“A couple of weeks ago. I’ve been keeping it quiet but I don’t seem to be able to put it out of my mind. I have nobody to share it with. As you know his mother died many years ago. Margot is very supportive but she doesn’t really understand.”

“I knew Raymond well. He and I spent some marvellous evenings at the Café Royal. I’m afraid we rather lost touch since the war started, but he was a wonderful, warm man, and he had a brilliant legal mind.”

“Thank you, Keynes. I didn’t know you and he were acquainted.”

“Do you have any information about how he died?”

“I received a letter from one of his men this morning, ordinary chap, but he was with Raymond at the end.” Asquith reached into his jacket and produced the letter. “Here, read it.”

Keynes took the letter. Beautifully written, it explained the events leading up to Raymond’s death. His company was involved in an assault on the German lines at Flers-Courcelette. Soon after leading his men out of their trench he was shot in the chest and fell to the ground. Although severely injured, with help he propped himself up, took out a cigarette and lit up, before waving the rest of the company on into battle. He then insisted on waiting for stretcher bearers, rather than being carried back to the trench by men who would otherwise be joining the assault. By the time he eventually reached the clearing station he had lost too much blood.

Keynes wiped a tear from his eye. “Prime Minister,” he said, “having known Raymond, nothing in this letter surprises me. He died an heroic death serving his country. No father could expect more of his son.”

“Thank you, Keynes.”

“Prime Minister, excuse me if I’m speaking out of turn, but this dreadful news must further focus our efforts to bring the war to an end. At the current rate, there’ll be nobody left of Raymond’s generation.”

“I know. I’m just not sure what more I can do.”

On his way back to the Treasury, Keynes’ mind was racing with the possible consequences of what he had just heard. He knew how close the Prime Minister had been to his son. He also knew how exhausted Asquith had been, even before Raymond’s death. He’d been Prime Minister for more than eight years; the job could not have been more difficult than it had for the last two. The vultures had been circling for some time and this blow could prove fatal. He was a politician of great experience, but he’d failed to marshal the political forces necessary for a negotiated peace. If Asquith couldn’t do it, nobody could, least of all his only possible successor.

Summer at Wissett had been wonderful. Vanessa had thoroughly enjoyed turning the dilapidated farmhouse into something habitable. Not only had she found somewhere to paint, which she did for several hours each day, but she’d also created a home in which Duncan and Bunny could relax. Both seemed happy, and even Duncan managed to take some enjoyment in the work. What she liked most about the house was its remoteness; not just its geographic location, miles from the nearest town, but the way it insulated its occupants from the relentless misery of the war.

It was a quite different life to the one she had been used to in London, where it had been impossible to escape the constant stream of visitors. She loved her friends, but when none brought with them any good news, life became rather wearisome. Here in the country she was, for the first time, entirely in control. It did mean keeping house for Duncan and Bunny, but she had help with that, and it was a small price to pay for her freedom, and for the chance to be with Duncan every day. Clive had visited once with Mary Hutchinson; they were unlikely to return though. He had complained endlessly about the cold and the lack of a daily newspaper. Vanessa had warmed to Mary a little, especially as she noticed that as they became more friendly, Clive became more irritated.

Keynes had been up a couple of times; his visits had been more enjoyable, even though he was there primarily to help Duncan and Bunny at their tribunal hearings. The first of these had been a disaster, one for which Keynes was entirely responsible. His inevitably intellectual advocacy on behalf of Duncan and Bunny failed to impress the local farmers in whose hands the fate of the two men rested. From her place in the public seats, Vanessa could see it was not going well and had tried to catch his eye to suggest a change of tack, but he bore on, the low point coming when he announced to the tribunal that Bunny’s mother had once met Tolstoy.

His next visit had been more successful, not least because the appeal tribunal at Ipswich consisted of educated men with some legal experience. Duncan and Bunny won their exemption, although the matter of whether their work could be considered of national importance was referred to the central tribunal in London. There was no question that they were actively involved in the production of food, the problem was their employment status; it was felt that self-employment was incompatible with the status of a conscientious objector. They would have to wait another two weeks for the final decision.

That evening, Duncan and Bunny retired early, so they were left to enjoy a rather good bottle of Armagnac which Keynes had brought back from Paris. Vanessa was worried they might have to move again. She was enjoying life in the country and should the central tribunal make it a condition of exemption that Duncan and Bunny find work on a farm owned by someone else, she wasn’t sure how easy that would be. Keynes reckoned that if the tribunal found against them they would have just two weeks to find alternative employment, otherwise they would be called up.

They’d been sitting in silence for some time when they heard a most peculiar noise in the distance. Neither could work out what it was, nor where it was coming from. Moments later, illuminated by the full moon, they were able to make out the hulking form of a Zeppelin floating serenely in their direction. It passed right over the farmhouse, low enough to cast a shadow. Vanessa was bewitched. She’d heard about the Zeppelin raids and the destruction they wrought, but she hadn’t imagined they could be things of such beauty and grace.

In the event, the Central Tribunal came to its decision rather too promptly. Duncan and Bunny would have to find formal employment. Vanessa had to move quickly. Clive had suggested the boys join him at Garsington where Philip Morrell had opened a ‘farm’ offering employment to a number of his wife’s friends who were in similar need.

Lytton Strachey was there, along with Lawrence and a number of other artists and writers, mostly reprobates as far as Vanessa was concerned. But Garsington was not an option: Vanessa couldn’t abide Ottoline and Duncan would rather be sent to France than spend another minute with Lawrence.

And so she found herself on a train to Lewes. Virginia had heard about a property not far from Asheham which was available on a long lease. She’d also heard that the owner of a nearby farm was struggling to recruit labour, all the local men having left for the war. Virginia had arranged an appointment with this Mr Hecks, who Vanessa hoped would have jobs for Duncan and Bunny. If a promise of employment could be secured she would then make enquires about the house.

Thanks for reading Maynard’s War. Subscribe for free to ensure you never miss a chapter. Or take out a paid subscription and help me to deliver chapters on time.

And if you’re interested in all things Bloomsbury, and specifically 20th century British art, do check out Victoria K. Walker’s Beyond Bloomsbury. It’s fabulous.

Wonderful Mark! And thank you so much for the mention ✨✨