Thanks for reading Maynard’s War, and a warm welcome to my new subscribers. Chapter 19 will be published next Sunday, Easter Sunday, 20th April at 11am UK time. Do please share with anyone you think might be interested - it takes but a click.

If you’ve only just discovered Maynard’s War and would like to start at the beginning, then please click this button:

June 1916

Keynes was having trouble concentrating. He’d been trying to remember the last time he’d had sex. There were noticeably fewer men about since conscription, and he was surprised how much of a difference it made. Throughout his time in London, and before in Cambridge for that matter, whenever he required male company he’d been able to find it without problem. In the last few months, however, it had become steadily more difficult, not to mention, risky: the last time he was out, a man he’d convinced himself was trustworthy turned out to be nothing more than a common thief. He was fortunate on that occasion that the appearance of two passers-by enabled him to escape, but the episode had put the wind up him. He hadn’t been out since, and wasn’t sure how he was supposed to satisfy his appetites without putting himself in mortal danger. In an unguarded moment, he found himself thinking about Edwin Montagu, but quickly dispatched that thought from his mind. Before it could wander off into such territory again, there was a knock at the door. “You busy old chap?”

Keynes looked up from his desk to see Basil Blackett standing in the doorway. “Not for you,” he replied. “Come in.”

Blackett pulled the heavy chair from its position in front of Keynes’ desk, around to the side so they could converse less formally. “You haven’t heard the news about the naval engagement?”

“No,” Keynes replied, “but from your tone I presume it is not good.”

“The Germans are claiming a rout. Total victory for their side. We lost six ships and they lost two.”

“And what are we saying?”

“That’s the problem, nothing really. Battle took place off Jutland. The news was already circulating in Germany while what remained of our fleet was making its way back across the North Sea.”

“And so our newspapers are reporting exactly what the German press is saying.” Keynes sighed. “Why are we so bloody incompetent at news management?”

“I don’t know, but it’s a mess, and even if it is all German propaganda, they got in first. It’ll be dreadful for morale.”

“If that number of ships have been lost, it’ll be dreadful for our finances too. Did they really have to be drawn in to a full scale sea battle?”

“Too good an opportunity to waste, apparently. Unanimous decision.”

“But the wrong one.”

“With hindsight, yes.”

“I’m sorry, Basil. I don’t mean sound so glum. God knows I wouldn’t have known what to do. That’s the problem with war: there’s never enough information to make a properly informed decision.”

“I’m not sure it would have made any difference. These military chaps seem to do everything on instinct.”

“Presumably it’ll make things harder for merchant traffic?”

“Yes. German U-boats will have the run of North Sea for the next few months.”

“I don’t suppose you have any good news for me?”

“I have, actually. Kitchener does want you to accompany him to Russia after all.”

Keynes had been desperate to get on the trip with Kitchener who was leaving for Orkney on Thursday to join HMS Hampshire for the voyage to Archangel. Though what he’d imagined to be a perfectly safe voyage now felt a little daunting.

The Archangel meeting was crucial. The Russians had suffered heavy casualties and were in desperate need of new arms supplies. The allies were in agreement over the need to support the Russians, but they needed to work out the financing. Keynes wasn’t entirely sure why the Secretary of State for War was leading the delegation.

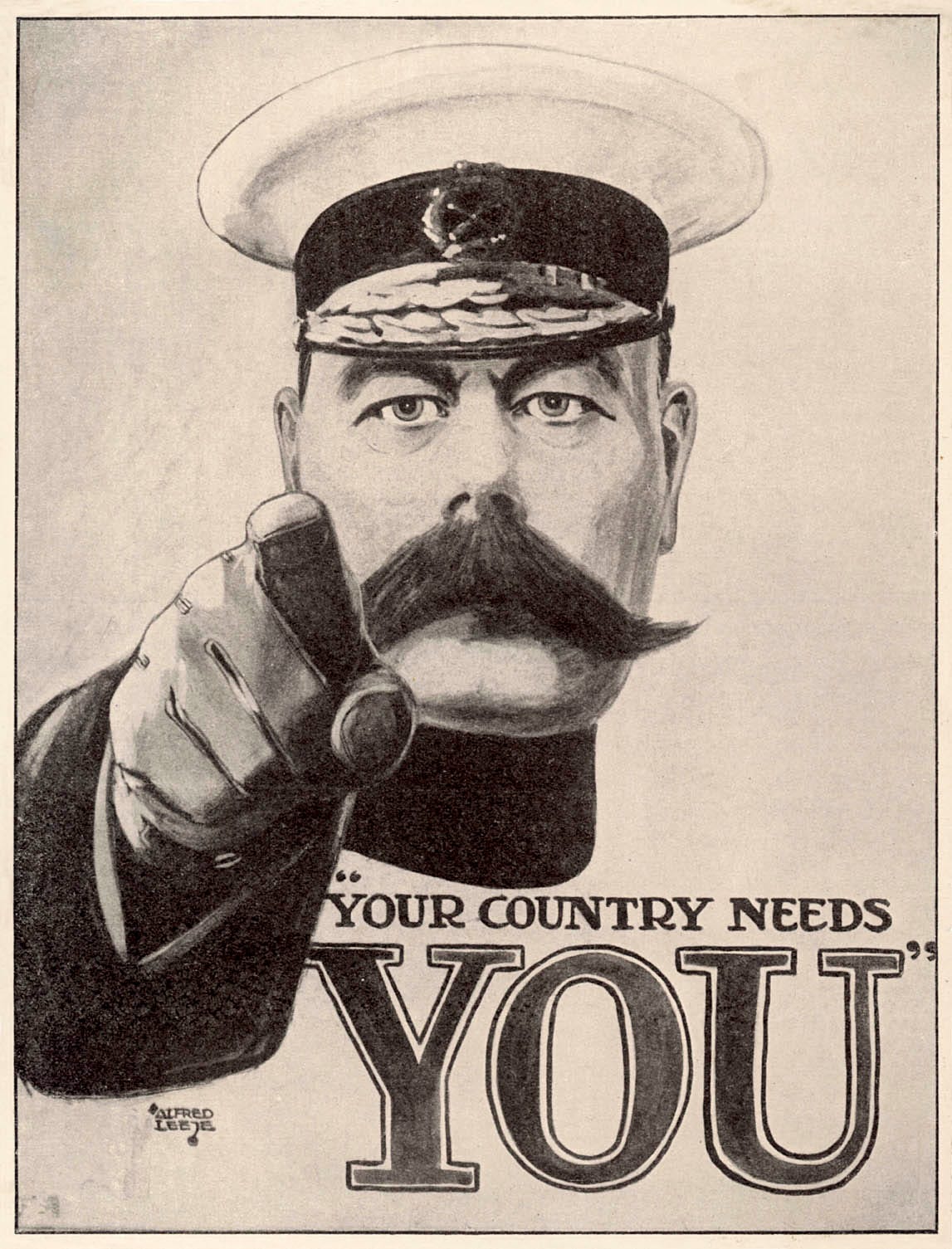

There were rumours Asquith wanted him out of the way so he could work directly with the generals, none of whom could stand Kitchener. It was impossible to remove him from his post permanently as he was exceptionally popular with the public.

Keynes thought him a fascinating man. Alone among frontline politicians, he had predicted the war would last at least three years and he was single-handedly responsible for the successful recruitment campaign that enabled the government to avoid conscription until well into the second year of the war. Kitchener’s reputation was immense, and this, Keynes assumed, was the reason he was going: it would send a strong message to the Russians that the allies were standing four square behind them. But it wouldn’t be enough simply to butter up the Russians. Whatever deal Kitchener was able to do, it had to be supported by a transparent finance arrangement and only Keynes could deliver that.

“You don’t fancy coming along, I suppose?” he asked Blackett.

“I’d love to but I can’t give you the time I’m afraid. Have you seen the schedule of official delegations in the next couple of weeks. They’ll be queuing up Whitehall if we’re not careful.”

“Not to worry. It’ll be good to get close to Kitchener. I’ve always wondered what makes him tick.”

As soon as Blackett left, Keynes wrote a letter to his parents to tell them about the trip. As usual he included as much detail as he could get away with; his father was always keen to learn about the negotiations in which he was involved.

Leonard looked once more at the letter as the train rattled through Strawberry Hill station. It had arrived a week ago with instructions that he report to Kingston Barracks today at 11am. He had lied to Virginia about where he was going: he rather wished he was meeting Morgan Forster for lunch, but that treat would have to wait, possibly for some time.

He arrived in good time and was shown to a chair in a corridor. There were about thirty other unfortunates sat on identical chairs. He assumed they were all in the same position: had they been enthusiastic about participating in the war, or unencumbered in their ability to do so, they wouldn’t have waited to be called up.

After a few minutes, a severe-sounding man in a crisp uniform ordered all those sitting on Leonard’s side of the corridor to follow him. They found themselves in a white-tiled room with a bench against one wall. Leonard was instantly back at school; he knew exactly what was about to happen. They were instructed to remove all their clothes and place them on the hooks above the bench: one hook per person, shoes to be placed under the bench. Once naked they were led into another, very cold, room where they had to stand until they were called in to see the doctor.

As he watched others disappear through the door in the corner of the room, Leonard remembered he had left Wright’s letter in his jacket pocket. His heart sank; he had been so confident it would get him off, he hadn’t properly considered the possibility that he could, within minutes, be enlisted in the army. The call-up letter had made it clear that unless he was found unfit for service on medical grounds he would not be allowed to return home. In this case his plan was to apply immediately for a commission in his brothers’ regiment, but it occurred to him that perhaps he should have told Virginia he might not be back for supper.

By the time his name was called he was freezing and his hands were shaking uncontrollably. The young doctor noticed this immediately and took him through a connecting door into a slightly larger room where a man in a Captain’s uniform asked about his trembling hands. He took the opportunity to explain that he had left Wright’s letter in his coat. Still shaking he was escorted back to the ante-room to collect the letter.

The senior doctor read it and gave him a thorough examination. By the time it was over, an orderly had come in with Leonard’s clothes. He was told to dress before being shown to another room where he was instructed to sit and wait. There was one other man there, a chap whose yellow skin suggested a severe case of jaundice. The inhumanity of the entire process appalled Leonard, though he didn’t doubt that this was just the tip of a very large iceberg. An hour later, a different officer appeared with a letter in an unsealed envelope. He handed it to Leonard and told him he was free to go.

Keynes was furious with McKenna. He simply couldn’t understand why the Chancellor would have pulled him off the Russia trip at the last moment. There were plenty of people who could have dealt with the Serbian delegation. He smelled a rat. He knew McKenna didn’t like Kitchener, but he also knew how important these negotiations were. Now there would be no Treasury representative in Archangel. Surely McKenna didn’t think the charismatic Kitchener would provoke in Keynes some sort of disloyalty. He’d been trying to see McKenna for two days, but the Chancellor was unavailable. Keynes had never been refused access to his boss like this. Something must be going on.

There was a cursory knock on the door and Blackett came rushing in. He looked white as a sheet. “What is it Basil?”

“Quite dreadful news, I’m afraid. The Hampshire has been sunk off Orkney. Only a handful of survivors. Kitchener is presumed dead.” Keynes couldn’t take it in. The two men looked at each other in silence.

“Are you alright old chap?” Blackett asked eventually.

“Er, yes,” Keynes said, running his hand through his hair. “Thank you for letting me know. I must get to the telegraph office at once. I neglected to tell my parents I wasn’t making the trip after all.”

Thanks for reading Maynard’s War. Subscribe for free to ensure you never miss a chapter. Or take out a paid subscription and help me to deliver chapters on time.

And if you’re interested in all things Bloomsbury, and specifically 20th century British art, do check out Victoria K. Walker’s Beyond Bloomsbury. It’s fabulous.