Thanks for reading Maynard’s War, and a warm welcome to my new subscribers. Chapter 15 will be published next Sunday, 23rd March at 11am UK time. Do please share with anyone you think might be interested - it takes but a click.

If you’ve only just discovered Maynard’s War and would like to start at the beginning, then please click this button:

February 1916

Keynes had been at his desk since half past six. He was the first to arrive and would be the last to leave. He had been reading papers, considering their content and writing memoranda for the growing roster of politicians who now regularly sought his council. It had been a particularly trying morning: too much thinking and not enough to show for it. Mind you, there was a great deal to think about: he’d never had such a strong sense of the world collapsing around him, nor felt under such pressure to do everything in his power to hold it together.

He wondered if any of his colleagues were similarly affected by the pressures facing the country. Surely they must recognise the gravity of the situation. Most had good brains after all, though he had long ago learned that intelligence was only one of several criteria by which a colleague’s competence should be judged.

He was surprised how few of the people he worked with were able to assess a problem in its full context; to see the big picture. Perhaps this capacity was a natural endowment which few people enjoyed. He thought this to be something of a tragedy, for if more people were able fully to anticipate the consequences of their decisions, they would be bound to make different ones and better outcomes might follow.

Keynes wondered if this deficiency was the consequence of some psychological shortcoming. He suspected that for many people the emotional cost of fully confronting reality was simply too much to bear. Most people’s consciousness, it seemed, was filtered through a valve which limited what they could see to what their psyche could cope with.

He himself must have been absent from school on the day these valves were given out. His own unfiltered consciousness, while giving him a distinct advantage over most of his colleagues, also had its drawbacks. It meant that in order to win an argument, or even just to get a point across, he had to approach any question from the rather limited point of view of whomever he was debating with. This meant constantly having to frame arguments in terms that other people could understand, even if it meant leaving out important information. And in the process of so-doing, he became guilty of over-simplifying problems that couldn’t be solved unless they were understood in their full complexity. He didn’t know if this theory had any merit, but it certainly helped explain why the politicians and the generals were making such a mess of the war.

It had been a beastly few weeks. The government had been tearing itself apart over the Military Service Bill which, having become law at the end of January, now obliged all bachelors and childless widowers between the ages of eighteen and forty-one to enlist. Since the bill had been mooted, Keynes had been under unremitting assault from his friends to give up his job. They had never really understood why he took it in the first place, but having seen him change his attitude to the war, they seemed confident he would now do the honourable thing. This made him feel under even more pressure, as if his mind had been made up for him.

He didn’t think any of them were pacifists in the true sense of the word, but they objected vehemently to the government legislating to remove from individuals the choice of whether or not to fight. He felt the same, and yet here he was actively assisting the government in its chaotic prosecution of an unjust war.

He wasn’t the only insider to have his loyalties tested. At Christmas, five members of the cabinet, including his boss, Reginald McKenna, had submitted their resignations. Although each was vehemently opposed to the war, they camped their objections to the Military Service Bill in more nuanced terms in the hope of widening their support base. They argued that the case for conscription was insupportable because its objective was to enable the expansion of the fighting force to sixty-nine divisions. Keynes had provided evidence that an increase to just sixty-two divisions was impossible without diverting resources from other essential activities. What good were an extra hundred thousand men if they couldn’t be fed and had no ammunition? It was obvious to Keynes there was an optimal number of military personnel which could be supported and therefore fight effectively. If that number were exceeded, not only would the additional troops be ineffective, but the entire fighting machine could grind to a halt. Asquith knew this, even if he was unable to admit it publicly. Keynes was convinced that Lloyd George knew it too, but the Welshman had his consciousness filter set permanently to a level guaranteed only to smooth his way into No.10.

For a tense few days at the beginning of January it seemed that the five Cabinet ministers would indeed resign. In the event only one of their number, the Home Secretary, Sir John Simon, carried out the threat. The others accepted Asquith’s olive branch of a promise to establish a cabinet committee to assess competing economic and military claims. Keynes knew the committee would achieve nothing. Once again he faced a dilemma: had McKenna resigned he would have gone too, but he felt immense loyalty to his boss and didn’t want to desert him. His decision to remain at McKenna’s side was in part influenced by his parents, who had been terribly upset at the prospect of his abandoning such a promising career on a point of principal, even though they shared his views.

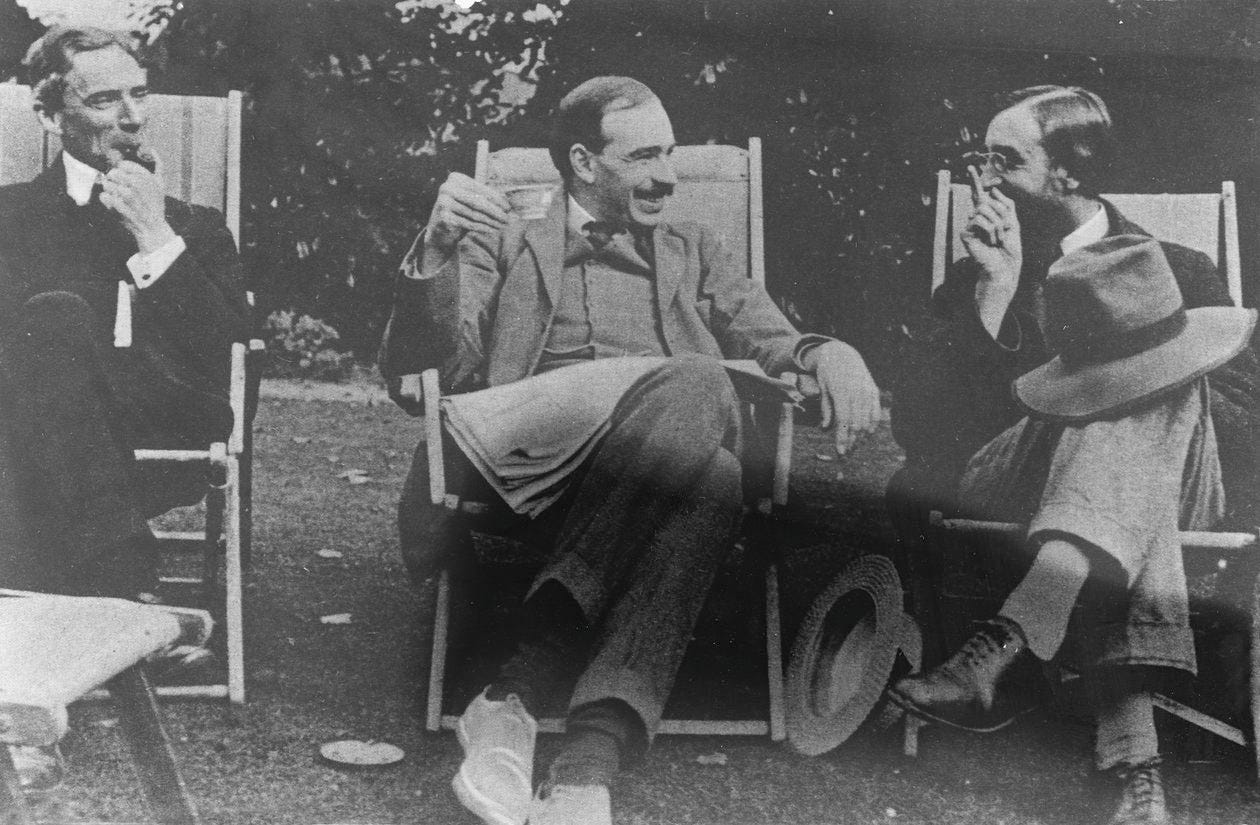

He looked at the clock above the door. It was ten to one; he needed to get his skates on. Lytton Strachey and Bertie Russell had engineered themselves an invitation to lunch. Knowing he would be under heavy fire from the outset and pleading lack of time, he had persuaded them to come to him. They would be dining in the bowels of Whitehall: Keynes thought Strachey, at least, would find the venue so fascinating he might forget the reason for the meeting.

He made his way down to the basement of the Treasury and into the tunnel connecting it to the bunker canteen which his guests would have to enter via the cleverly disguised entrance just off Whitehall. He was a couple of minutes early so elected to wait for them outside. They soon came into view, heads down in earnest conversation trying to negotiate their way through the heavy traffic. As they approached, he beckoned them towards the entrance and warm greetings were exchanged.

“Good of you to make time for us,” Russell said as they took their seats around a plain wooden table.

“Always a pleasure Bertie, just as long as you don’t have that dreadful man Lawrence with you.” Strachey let out one his irritating squeaky laughs. “Do I amuse you Lytton?” Keynes asked, sternly.

“Maynard you always amuse me. Indeed, you inspire me. Whenever we meet my mind is set racing for a period of never less than forty-eight hours.”

Keynes decided to take the initiative. “So, somebody decided to send out the big guns to force me to resign.”

“Really Maynard,” Strachey said, “there is no question of forcing you to do anything. It is this government which has passed a bill which forces men of good conscience to fight against their will. We are simply here to appeal to your good conscience.”

“But do you really think my departure would cause more than a few ripples across Whitehall?”

“I think you underestimate your importance,” Russell said.

“In which case, do you not think I’m better placed to influence from within. You know I’m opposed to the war. It was me who provided McKenna and the other rebels with the information that enabled them to have their threats of resignation taken seriously.”

“But they withdrew their threats without obtaining any change of policy,” Russell said.

“And the bill passed without amendment,” Strachey added.

“I know,” Keynes was momentarily lost for words, “but I can still make more of a difference on the inside. It’s imperative that Asquith remain Prime Minister, and a strong one. If Lloyd George were to take over the war effort would be doubled, casualty figures would rise exponentially and the country would be bankrupt. And the war would be lost within a year. Do you not see what a difficult position I’m in?”

“I presume you’re still on good terms with Edwin Montagu?” Strachey asked, pointedly.

“Yes, of course. Why?”

“Did you read the text of the speech he gave the other week?”

“I don’t think I’ve read anything so unpleasant in my life,” Russell added.

“I had the misfortune to hear the speech delivered. I was no less appalled than you Bertie. You know I detest that kind of militaristic jingoism. It’s all the more appalling because I know Montagu doesn’t hold those views. The speech was made for political reasons. But if McKenna were to resign, if Grey went, Runciman and Birrell, there would be nobody to temper those vile opinions. That is why I have resolved to stay.”

“The problem, Maynard,” Strachey said, “is that we’re not entirely sure we believe you.”

“I’m sorry? You think I’m lying about my motives?”

“Well,” Russell said, “you have mentioned how much you enjoy the work. I wonder if your judgment isn’t clouded by that fact.”

“I can assure you it is not. Had McKenna resigned I would have gone with him. But as long as he’s in the game, there is still hope and I shall stay.”

“In that case, I’m not sure there’s anything more to say,” Russell said.

“I should think there is.” Keynes replied.

“I’m sorry?”

“You may have noticed, Bertie, that there is a growing band of MPs who are demanding the government sue for peace.”

“And is there any prospect of their argument being taken seriously?” Strachey asked.

“I don’t know, but surely it’s worth a try. Unless we want the war to go on for another two or three years.”

“Well, I’ll look into it,” Russell said, apparently miffed he now appeared to have lost an argument he had felt sure to win.

“You do that, and let me know if I can be of any help,” Keynes said firmly, succeeding in bringing the conversation to an end.

He elected to walk back to his office above ground. He was tired of having to defend himself to his friends. Russell and Strachey both had exceptional minds, but neither had any idea of the complexities of the real world, the world of politics and war; his world.

He wasn’t entirely immune to their arguments, and thoughts of resignation were never far from his mind. But what possible good would a principled resignation do? And there was now a further complicating factor: as long as he remained in the Treasury he would be exempted from military service. Were he to resign he would no longer enjoy that protection. He decided to write to the local tribunal, applying to be exempted on the grounds that he held a conscientious objection. Then, if his conscience did ultimately force him to resign from the Treasury, he might still succeed in avoiding the draft.

Thanks for reading Maynard’s War. Subscribe for free to ensure you never miss a chapter. Or take out a paid subscription and help me to deliver chapters on time.

And if you’re interested in all things Bloomsbury, and specifically 20th century British art, do check out Victoria K. Walker’s Beyond Bloomsbury. It’s fabulous.