Thanks for reading Maynard’s War, and a warm welcome to my new subscribers. Chapter 14 will be published next Sunday, 16th March at 11am UK time. Do please share with anyone you think might be interested - it takes but a click.

December 1915

Keynes was thrilled to be asked back to the Asquith’s country home in Berkshire. He must have created a good impression the first time round. Opportunities to impress the Prime Minister were thin on the ground at work, so to be included in his social circle was not only an honour but a clear sign of his increasing status in Whitehall. On his first visit he’d got on particularly well with Mrs Asquith who was an enthusiastic, if not especially competent, bridge player. Nonetheless she and Keynes had won a considerable amount of money off his old friend Edwin Montagu who would be there again, this time with his new wife, Venetia. He was, however, a little apprehensive as the Asquiths’ daughter, Elizabeth, only eighteen, would be completing the party. As he was unaccompanied she would presumably be his ‘pair’ whenever any pairing was required.

He was the last to arrive. This was no great surprise as he seemed to spend more time at work than any of his colleagues. After a quick change he descended to find the others waiting for him. Margot Asquith was the first to greet him. “There you are Maynard, we thought you must have got lost. Did you have a frightful journey?”

“No actually,” he replied. “In fact, I made very good time. A rather heavy workload at the Treasury prevented my leaving earlier.”

“Keynes, good to see you,” the Prime Minister advanced past his wife and shook his hand, “what, um, what would you like to drink?”

“I’m very grateful for the invitation, Prime Minister,” Keynes said, and, noting that Asquith must have starting drinking while he himself was still elbow deep in Monday’s cabinet papers, added that a gin would be very nice.

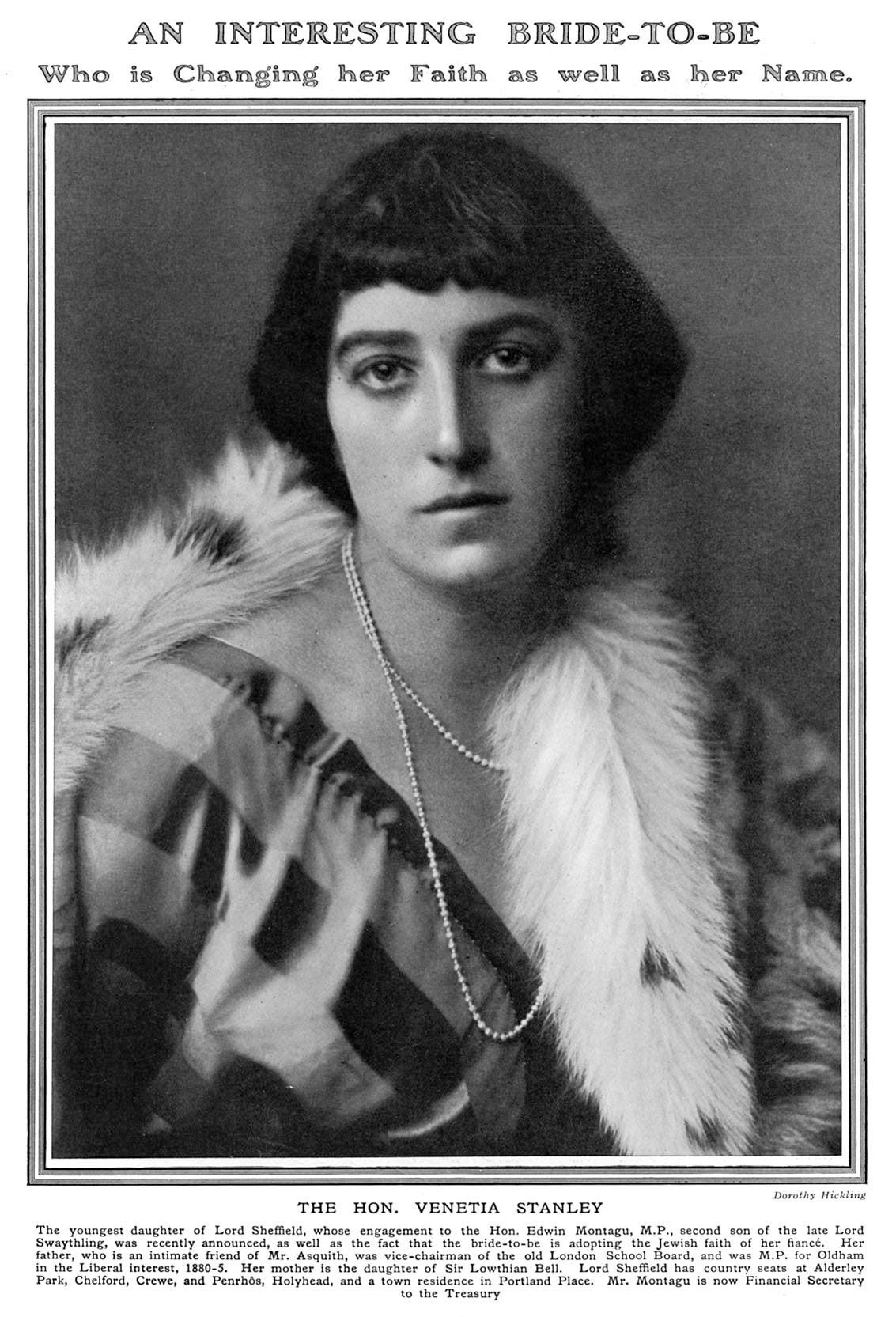

As Asquith followed his wife back to the sofa where he’d left his own drink, Montagu came over to introduce Venetia. “It’s a delight finally to meet you,” Keynes said, resisting the temptation to add that he’d heard a great deal about her. He had, of course, but not from Montagu. It was widely believed that during a trip to Sicily three years earlier, Montagu and Asquith had both fallen in love with Venetia, who was accompanying them as she was a friend of Asquith’s elder daughter, Violet. It was not altogether clear that Venetia, despite being half the Prime Minister’s age, hadn’t reciprocated his feelings, and so it had come as something of a surprise when, after several attempts, Montagu had finally had his proposal of marriage accepted.

Although Keynes regularly saw Montagu at the Treasury, they rarely spoke about personal matters. This was rather curious because he was reputed to be the greatest gossip in Whitehall. Presumably he wasn’t as reserved in his conversations with other colleagues, or perhaps, despite their longstanding friendship, he remained wary of Keynes. They had certainly never spoken of his relationship with Venetia, so once she had returned to her conversation with Elizabeth Asquith, he was pleased to have Montagu to himself. “I must say Edwin, she really is as impressive a creature as people say. You must be very happy.”

“Thank you, Maynard,” Montagu replied. “Yes, we are both very happy.”

“Tell me, did she have to convert?”

Montagu looked uncomfortable at the question. “She has converted, yes. Not that it was my wish.”

“Ah,” Keynes said, “question of inheritance.”

“Anyway,” Montagu said, “married life is suiting us both very well. I consider myself most fortunate to have found someone who shares my interest in politics.”

Keynes recalled a conversation with Basil Blackett about high-level concerns over Asquith’s prolific correspondence with Venetia from whom he appeared regularly to seek counsel on important matters of state. It occurred to him that the new Mrs Montagu was possibly better informed about government business than her husband. And then there was the question of Montagu’s sexuality. He was four years Keynes’ senior, and while their paths had crossed at Cambridge, they hadn’t been part of the same circle. Lytton Strachey had been adamant that Montagu was a bugger, but despite exhaustive efforts, had failed to gather the first hand evidence required to convince his friends of the fact.

It remained a mystery why anyone would choose to remain in the closet at Cambridge. In his experience, every man who preferred male company, while fully aware of the need to be careful, was able to rely absolutely on the discretion of his peers, even of chaps like Leonard Woolf whose sexual tastes were decidedly conventional. It all made Keynes slightly suspicious of Montagu even though they got on well. If Montagu’s marriage was intended as cover for his homosexuality, what on earth could have persuaded Venetia to go through with it? She could have had any man in London.

Before Keynes had time to change the subject, Montagu excused himself to make a phone call. Noticing the Prime Minister was receiving a stern talking to from his wife, he made his way to the window where Venetia introduced him to Elizabeth.

“Maynard,” she asked, “didn’t Edwin tell me that you know some writers?”

“Yes, one or two, why?”

“Elizabeth was just telling me that she is a writer.”

“Actually,” Elizabeth interrupted her, “I hope to be a writer.”

“But you presumably have written something. How else would you know that you’d like to be a writer?” he asked.

Elizabeth looked slightly embarrassed but replied firmly. “I have indeed Mr Keynes. In fact I’ve recently written a play with the help of Mr Bernard Shaw. Do you know him by any chance?”

“I have met him on one or two occasions, yes. Feisty fellow, rather likes the sound of his own voice, but sincere I think.”

“Oh, he is Maynard,” Venetia said. “If you can get through the bluster, he really is quite charming. And one of the few successful men of my acquaintance who actually takes the time to listen to what women have to say.”

“In marked contrast to that dreadful man Lawrence, then.” Keynes said.

“You know Mr Lawrence too?” Elizabeth enquired.

“I do, Miss Asquith, though it’s not an acquaintance I hope to renew.”

Elizabeth looked slightly disappointed at this news, but persevered. “And do you know any other writers?”

“Well,” he said, happy to indulge her enthusiasm, “my lodger, Miss Mansfield, she’s not much older than you but she’s had some success with her short stories. I think she has a bright future.”

“I should like to read her stories,” Elizabeth said, gratefully.

“Then there’s Morgan Forster, he’s a very good friend. You may have heard of him?”

“Oh indeed,” Elizabeth said excitedly. “I’ve read all of his novels, he writes so beautifully.”

Keynes was starting to find the game a little too easy but couldn’t bring himself to stop. “And then there’s my dear friend Mrs Woolf. Of course, she’s only just published her first novel and it’s not done terribly well, but several critics think she is exceptionally talented.”

“Oh my goodness, Virginia Woolf? Mr Keynes, this is very forward of me but might it be possible to arrange a meeting with Mrs Woolf. I’ve just finished The Voyage Out and it’s quite the most original novel I’ve ever read.”

“I’ll have a word,” Keynes answered, smiling “I’m sure Virginia would be delighted to make your acquaintance.”

“Oh, thank you,” she said, embracing him before rushing off to tell her parents the news.

Venetia looked at him, “I must say, Maynard, I didn’t realise you were quite so well connected.”

“I suppose I am. But then it’s a small world, don’t you find?”

As they sat down to dinner that evening, it occurred to Keynes that he hadn’t thought of the war for more than three hours. The possibility of such escape was a great relief; no wonder the Asquiths chose to spend every weekend out of London. But he also felt rather guilty. Everything here was just as it would have been before the war: the beautifully manicured gardens, the endless supply of first class wine, the delicious food, a full complement of servants. He wondered how many of them would be able to avoid the draft should the bill pass in January. No wonder the Prime Minister was so anxious to avoid conscription.

Around the small dining table Keynes found himself seated next to Elizabeth, with Margot Asquith at the end of the table to his right. It soon became clear that the Prime Minister’s wife would have his ear for much of the evening. “Maynard,” she began, “I had you seated next to me because there is something we need to talk about. Last weekend Herbert insisted we visit Philip Morell and his wife at Garsington, it’s an easy drive from here. I believe you know them?”

“I do, although I have to confess to knowing Lady Ottoline rather better than I know her husband.”

“Yes, well it was she I wanted to talk to you about.”

“Oh really? In what regard?”

“I would have thought it was obvious. Do you not think the woman quite mad?”

Keynes laughed before realising Margot was being serious. “I believe she is totally mad,” he answered, “but not in a way that need give cause for concern.”

“Really?” Mrs Asquith gave him a quizzical look.

“Yes. You see there’s mad and there’s mad. Ottoline deliberately sets out to live her life in a way that defies conventional mores. Those of us for whom adherence to such mores is important can find this unsettling. And when we try to understand her behaviour, we are forced to the conclusion that she is mad. And she may well be, but it’s a form of madness which is perfectly harmless. And of course none of us are obliged to spend time in her company.”

“That is true, but my problem is that Herbert seems rather to like her peculiar behaviour, particularly the way she encourages her guests to act like children.”

“But Margot, your husband carries an unimaginable weight on his shoulders. Perhaps he needs to let his hair down from time to time?”

“Yes, I suppose you’re right. And in fact I can cope with most of it. But that silly man doing his ridiculous dance around the pond in the middle of the afternoon. He hadn’t even been drinking.”

“I suspect you are referring to Mr Lytton Strachey.”

“And do you know him?”

“Rather too well, I’m afraid. We were at Cambridge together. And I grant you he is quite mad, but he also has a brilliant mind and can be exceptionally good company, when he’s not dancing.”

Mrs Asquith laughed, rather loudly. “I shall have to take your word for it. I remember now, he came with a Mr and Mrs Bell, also friends of yours?”

“Mrs Bell yes, her husband, less so.”

“I didn’t speak to him, but Herbert had the misfortune to be seated next to her at dinner.”

“Misfortune?”

“Yes. During the soup she turned to him and asked his profession.”

“Oh that sounds just like Vanessa. What did he say?”

“He said he was in politics, to which Mrs Bell replied: and do you hope to run for parliament one day? At that point Herbert felt he had to come clean.”

“Oh dear. How did he break the news?”

“Most graciously, as you would expect. Madam, he said, it is already my great honour to serve you as Prime Minister.”

“Presumably at that point Vanessa excused herself?”

“Missed the entire fish course. But Maynard, you mustn’t say anything.”

Thanks for reading Maynard’s War. Subscribe for free to ensure you never miss a chapter. Or take out a paid subscription and help me to deliver chapters on time.

And if you’re interested in all things Bloomsbury, and specifically 20th century British art, do check out Victoria K. Walker’s Beyond Bloomsbury. It’s fabulous.