Thanks for reading Maynard’s War, and a warm welcome to my new subscribers. Chapter 12 will be published next Sunday, 9th March at 11am UK time. Do please share with anyone you think might be interested - it only takes a click.

November 1915

Since his return to work, Keynes had found politics to be getting in the way with frustrating frequency. The difficulty centred around the fractious relationship between his old boss, Lloyd George, now Minister of Munitions, and his new one, Reginald McKenna. Keynes and McKenna got on exceptionally well; not only did they often anticipate what the other was thinking, their views nearly always coincided. His relationship with Lloyd George, on the other hand, had gone from bad to worse, although it was not as bad as the one between the new Chancellor of the Exchequer and his predecessor.

Despite his reluctance to take Keynes’ advice, at the Treasury Lloyd George had at least taken a prudent approach to financing the war, resisting calls to spend more in pursuit of a quick victory. But since taking responsibility for armaments he had changed his tune completely, making endless demands that the government increase war spending, and picking fights with McKenna at every opportunity. In doing so, Lloyd George was aligning himself with senior Conservatives in the coalition and against the leadership of his own Liberal Party.

The question of conscription was also looming large. Keynes was opposed for both personal and strategic reasons. The thought of Duncan or any of his friends being compelled to fight upset him terribly. He thought it deeply illiberal to use legislation to force people to go to war. McKenna shared Keynes’ view - both knew it would signal a victory for Lloyd George who was too readily seduced by arguments that victory was simply a question of increasing troop numbers.

There was already ample evidence that the generals were unable to produce results to match their ambitions, regardless of the resources put at their disposal. Each time more troops were committed, there was a substantial increase in casualties for no gain in territory. That the Germans were suffering similar losses was no consolation, as the front invariably failed to move any closer to Germany. When Keynes tried to point this out to Lloyd George, he had stormed out of the room, bringing the reception at which Keynes was a guest to an abrupt end, and not endearing him to his colleagues, many of whom were still on their first glass of champagne.

Nonetheless, with the Gallipoli campaign lurching from one disaster to another and the Russians failing to make any headway in the east, the French were demanding that efforts on the western front be redoubled. So Keynes found himself in a bind. He couldn’t see how Britain could fund the war beyond the end of 1916 even at comparatively low levels of spending, but neither did he believe victory was possible within a year even if the allies did go for broke, conscription and all.

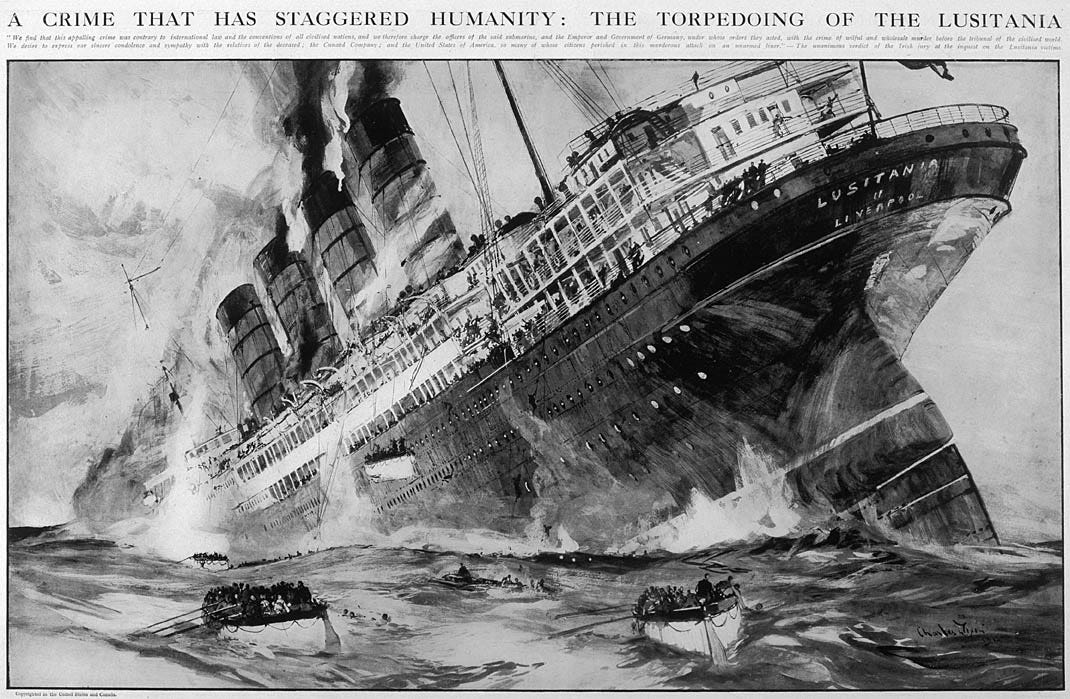

For a short time after the sinking of the Lusitania, it seemed possible the Americans might lend more to support the war effort, but inexplicably, President Wilson had chosen to turn the other cheek, making a speech in which he urged his countrymen that the proper response to such unprovoked aggression was for the country to assert its moral superiority as a peace loving nation and do precisely nothing. “There is such a thing as a nation being so right that it does not need to convince others by force that it is right,” Wilson had said. There had been nothing in the speech about the importance of remembering who your friends are.

Keynes had to stick to what he knew. The prospects for funding the war in the long term were extremely uncertain. He knew this advice would hand a victory to Lloyd George and force Asquith to commit more resources now. It would also mean conscription within weeks. The thought appalled him, but in the absence of an alternative he had to do the job he was paid for. He and McKenna had been over it repeatedly and always came to the same conclusion.

At least the Prime Minister had some sympathy with their position. If a swift victory didn’t follow, their jobs would be safe and they could continue to make their best efforts to save the country from oblivion.

Vanessa was grateful that Keynes had made it for dinner. She had been dreading the evening after receiving Lytton’s note. He’d had one of his turns and wouldn’t be joining them. Had Keynes not been able to make it, it would have meant a dull evening with only Clive for company. Duncan and Bunny were on their way to Paris, where Duncan had a commission to design scenery and costumes for a production of Pelleas et Melisande. Bunny, reluctant to return to his work for the War Victims Relief Fund, had heard about a research job in Paris and had decided to tag along.

Dinner was over and had been cleared. It had not been one of Mrs Jenkins’ best stews. This had become plain when Keynes felt it necessary to retrieve an eyeglass from the bureau. After much squinting and pushing around of vegetables he was able to confirm to Vanessa that meat was entirely absent from his plate. Vanessa was glad he took the variable quality of the food in good humour. It put Clive in a terrible sulk, usually with a demand that Mrs Jenkins be dismissed.

“So what entertainment do you have planned for me?” Keynes asked, lighting a cigarette.

“Oh,” Clive said, looking at Vanessa.

“It was Lytton’s turn to choose,” Vanessa replied blankly.

“I suppose we could just talk,” Clive suggested.

“Really Clive,” Keynes said, “we’ve been talking for well over a decade now and I’m not sure any of us have benefitted from it. In any case, it’ll only end up with you two berating me for my work at the Treasury.”

“Oh poor Maynard,” Vanessa said. “I promise we won’t berate you tonight. I know, that Shaw play we never got around to reading last year. I came across the scripts the other day. Shall I fetch them?”

“Why not,” Keynes answered, animatedly, “I fancy a bit of GB.”

Returning with the play scripts, Vanessa passed one to Keynes and dropped another into Clive’s lap, a gesture guaranteed to irritate as he was struggling to light his pipe.

“Right,” she said, scanning the first couple of pages. “Oh, there are only two characters in the first scene. Maynard, you read Gregory and I’ll read Mrs Lunn. Perhaps by Scene Two Clive might finally have some fire in his pipe and be able to read one of the other parts. Ready?”

“Ready,” Keynes said, as Clive struck another match.

As Vanessa took a preparatory breath there was a loud bang on the front door. “Oh, for crying out loud,” she said, “who can that be?” Aware that Mrs Jenkins would be unlikely to make the effort, she went herself. As she opened the door, Duncan, who had evidently been leaning against it, collapsed to the floor at her feet. “Clive, Maynard, come quickly,” she shouted.

“What on earth can have happened,” Keynes said as he and Clive hauled Duncan to his feet. They helped him into the sitting room and sat him down.

“Clive, fetch some water will you,” Vanessa instructed. She knelt in front of Duncan and held his hand. “Now Duncan, tell us what happened.”

Before he could speak a word, he burst into tears. Vanessa looked at Keynes. They had both seen Duncan like this - probably another row with Bunny. “It was just too awful,” he said eventually.

“Just tell us what happened,” Keynes said softly.

“It was when we arrived in Dieppe. Bunny and I became separated.”

“What do you mean separated?” Clive asked, handing Duncan a glass of water.

“We were going through the barrier where they check your passports and two of the officials just grabbed me and bundled me off.”

“But why would they do that?” Vanessa asked.

“I don’t know. They asked all kinds of questions, in a really aggressive fashion. I got very angry with them because I didn’t understand what they were saying. But that just made things worse. First they accused me of being a German spy, so I told them I despised the war, and wouldn’t spy for anyone. Then they accused me of being a pacifist and an anarchist. I said I was a pacifist, but certainly not an anarchist. I mean, what an absurd thing to suggest.” Keynes looked at Vanessa. “And then they said they would have to hold me while they made further enquiries, and if it was confirmed that I was an anarchist I would be sent to a prison camp for the duration of the war.”

“That’s outrageous,” Clive said.

“So what happened?” Vanessa asked.

“They locked me in a stinking room for several hours. When they returned they gave me the option of a prison camp or immediate deportation under escort. I had no choice but to accept deportation.”

“But were you not able to explain to them why you were going to Paris?” Keynes asked.

“I tried. I showed them the letter of appointment from the theatre and the Foreign Office letter you got for me.”

“And it made no difference?”

“None at all. They tore them both up.”

“So you had to come home under escort?”

“Handcuffed to a French brute carrying a pistol. It was awful. Soldiers and other passengers calling me every name under the sun. I’ve never heard such abuse.”

“It must have been a relief to get back to Dover,” Clive said.

“It was even worse in Dover. I was kept under guard until they put me on the train. The abuse from the British soldiers, it was all too much. I just don’t understand how people can be so foul. I have done nothing wrong. I’m an innocent.”

“Maynard,” Vanessa said, “surely we can do something about this. It’s outrageous that a British citizen be treated in this way.”

“I agree, Vanessa. And I have a great deal of sympathy, Duncan. In more normal times I’m sure we could insist the authorities do something. But we are at war. And I’m afraid you didn’t help yourself by admitting your pacifism.”

“But surely being a pacifist is better than being a spy?”

“Probably not in the opinion of your interrogators.”

“Well I think it’s dreadful,” Vanessa said. “You really must try to do something, Maynard.”

“I will make some calls. But whatever happens, I doubt very much that Duncan will get to Paris in time to complete his commission.”

“God, I don’t care about that. I’m never going to France again.”

“But why did they pick on you in the first place? That’s what I don’t understand,” Vanessa asked.

“I imagine those yellow trousers might have had something to do with it.’

“Oh, really Clive. You do say the most stupid things.”

“I think I might just go to bed,” Duncan said, pushing himself up out of the chair. Vanessa took his arm and helped him towards the stairs.

“I’m really not sure what to make of it all,” Clive said to Keynes as they were left alone.

“I’m afraid it’s the kind of thing that happens in war. The rules of civilized behaviour are suspended, at least in the eyes of people like the thugs who picked on Duncan.”

“There must be something we can do to bring this dreadful war to an end.”

“I am doing everything in my rather limited power, Clive. But it’s not easy.”

Thanks for reading Maynard’s War. Subscribe for free to ensure you never miss a chapter. Or take out a paid subscription and help me to deliver chapters on time.

And if you’re interested in all things Bloomsbury, and specifically 20th century British art, do check out Victoria K. Walker’s Beyond Bloomsbury. It’s fabulous.

Just a note. Lawrence dined with Russell at Trinity on the Saturday night. At midday on the Sunday, Russell took him into Kings and - as Keynes was still alseep - Russell began to write him an invitation for that (Sunday) night. Enter Keynes, in pyjamas. Not much conversation, I guess, just the invitation to dinner. That Sunday evening was when Russell and Keynes talked to Lawrence. Lawrence went back to Greatham on the Monday. john