Thanks for reading Maynard’s War, and welcome to my new subscribers. I hope you enjoy this latest chapter. Chapter 9 will be available next Sunday, 16th February at 11am. Please do share with anyone you think might be interested. It takes but a moment to click like, restack or the share button. Thanks, Mark

June 1915

Keynes was regretting having turned down Vanessa’s offer of his old room at Gordon Square. Living at such close quarters to Duncan would have been difficult, but at least there would have been someone to look after him in his hour of need. The move to his new home in Gower Street had been forced upon him. He had previously taken lodgings not far away in Great Ormond Street, but those were actively superintended by a rather ferocious landlady.

He might still be there had he been more discreet and allowed her to believe that his overnight visitors were female, but one morning he overslept and, late for work, he and his guest had to leave in a hurry, still dressing as they hurtled down the stairs only to run into the redoubtable Mrs Reynolds polishing the doorstep. It seemed to take an age for the two of them to manoeuvre past the woman and out into the street, during which time her expression changed from one of incredulity to hostile anger.

When Keynes returned home that evening he found a note under his door explaining that his tenancy was at an end, and making clear that if he did not vacate the property by Saturday next, she would have no choice but to inform the authorities.

He had often imagined a courtroom scene in which, representing himself, he exposed the absurdity of the homosexuality laws. He always won the argument, but still ended up going to jail. He cursed himself for being so careless. Even if he did vacate the premises as instructed, Mrs Reynolds, who was aware he worked for the government, might nonetheless pass on news of the episode to her friends.

He had decided to find accommodation where nobody could snoop on his private affairs. So here he was, in a rather unloved house, seriously ill and feeling utterly miserable. He hadn’t realised how quickly one could go from rude good health to being, apparently, at death’s door.

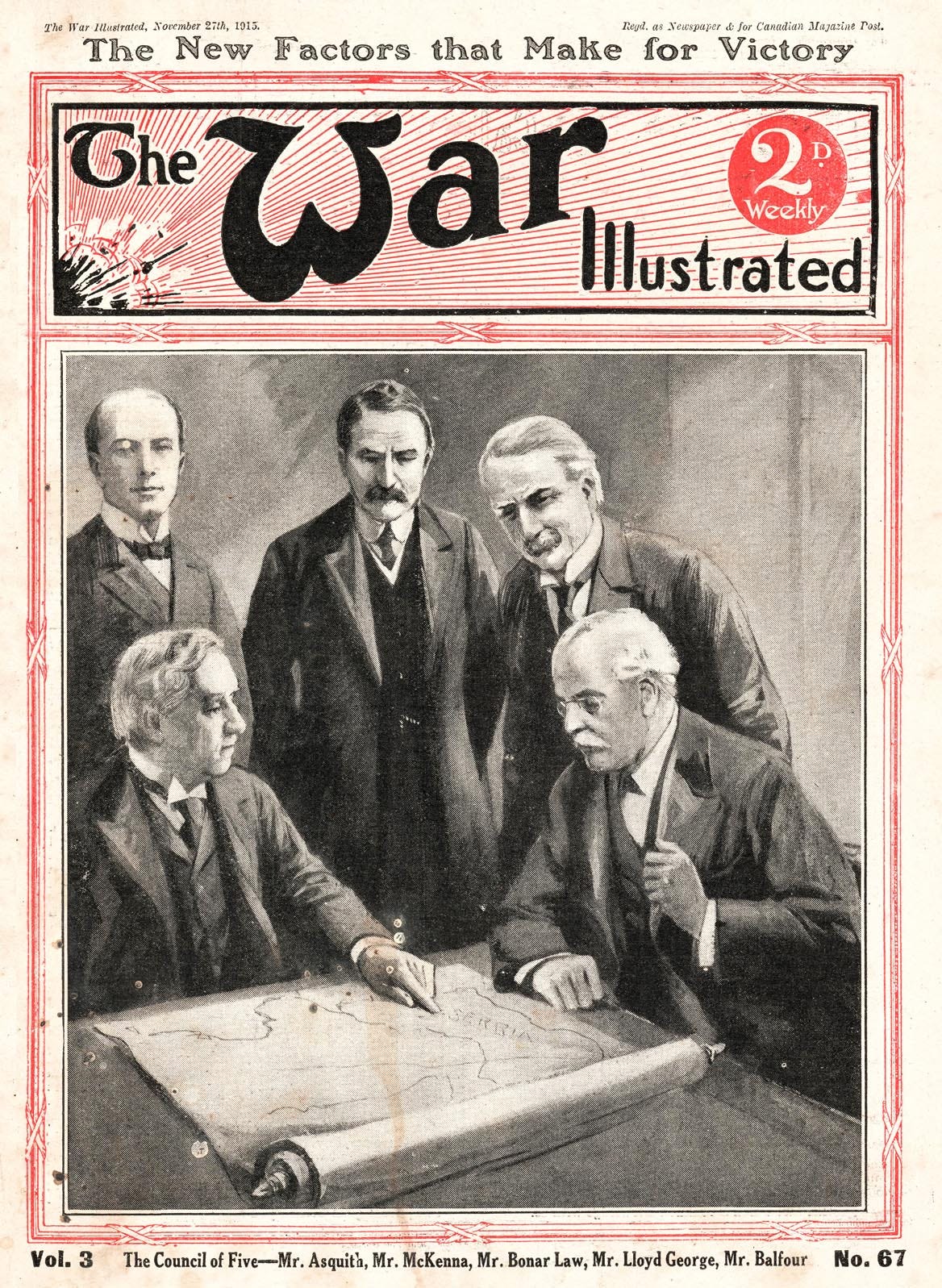

Things had been looking up after the change of government. In order to placate the Conservatives, who were invited into coalition, Asquith had to move Lloyd George from the Treasury. Keynes was delighted that Reginald McKenna had replaced him as Chancellor. One of McKenna’s first tasks was a meeting in Nice with the Italian Finance Minister and Keynes had accompanied him. The meeting had gone well, but on his return he began to feel distinctly unwell. After some delay, a perforated appendix was diagnosed, his condition becoming suddenly so grave that emergency surgery had to be carried out in his bedroom at Gower Street. The place hadn’t smelled the same since.

He had recovered quickly from the surgery and was starting to do some light work when he was struck down by a bout of pneumonia, again becoming so ill that his mother had to come down from Cambridge to look after him. And then yesterday, just when he was beginning to feel properly better, came the news he’d been dreading more than any other. His dear friend Feri Bekassy had been killed fighting on the eastern front. This was more than he could bear.

He had first met Bekassy when the Hungarian came up to Cambridge in 1911, the year Keynes was awarded his fellowship. Bekassy had a brilliant mind and they quickly became friends. It was Bekassy whom Keynes had to thank for properly introducing him to poetry. He seemed to have read everything, not just the English poets and those of his native Hungary. And he wrote the most sublime poems himself, verses that immediately opened up a new world of language and meaning. In the summer of 1912, Keynes had been delighted to accept an invitation to spend some time at his parents’ home in Hungary. It had been a wondrous two weeks: invigorating country walks and earnest discussion about poetry and the politics of eastern Europe, a subject about which he knew little.

And now his friend was gone, at just twenty-two. Not only was he bereft, but he also felt entirely responsible. When war had broken out, the Hungarian’s patriotic instincts persuaded him he should immediately return home and join up, but he couldn’t afford the fare to Hungary and so he asked Keynes to lend him the money.

The problem was not that his friend would be taking up arms for the enemy, rather the thought of this beautiful young man coming to harm. Despite his intellectual brilliance, Bekassy was too young to make a rational decision about the war; like so many he saw it as a glorious endeavour, an experience not to be missed.

Keynes had discussed his dilemma with Bunny Garnett, whose counsel he had come to respect. Bunny had urged him not to pay Bekassy’s passage. He had the opportunity, if not directly to save a life, then to prevent the loss of one. Keynes agreed but was unable to persuade Bekassy. When it became clear his friend would find a way to return to Hungary without his help, he gave him the money. He hadn’t done so recklessly or without due consideration, but now the guilt was unbearable.

This was his first real bereavement. He had never previously understood how such a loss could affect a person. He did now, and he was determined to throw off this wretched pneumonia so he could return to work and do everything possible to bring the war to an end.

Duncan was hysterical and Vanessa knew he would need careful handling.

“I don’t understand how he could do it to me. To just leave, barely say goodbye, and go off to the war, after all he’s said against it. I hate him.”

Though Bunny despised the Germans, he held the British Government equally culpable for its failure to stop the slide to war. He didn’t have a romantic view of war, nor was he motivated by loyalty to his country; but he wanted to experience more of life than a career in science was likely to provide. In the event, having considered joining the Officers’ Training Corps, Bunny had decided to volunteer for the Friends’ War Victims Relief Mission which would take him to France, to an area not far from the front line where he would be helping civilian casualties. It was two weeks since his departure and Duncan had heard nothing.

“Duncan darling,” Vanessa answered, “it isn’t something he did to you. It was something he felt he needed to do for himself.”

“Well he shouldn’t be so bloody selfish.”

She had reflected a great deal on the comparative levels of selfishness among the men she knew, and they were all as bad as each other. “I’m sure he’s come to no harm, he probably hasn’t had the time to write, or perhaps he has written. Lord knows what the postal service is like out there. I imagine they’d prioritise mail from troops serving on the front line.”

“Vanessa,” he looked up at her accusingly, “isn’t it obvious to you? Bunny doesn’t love me. If he did he wouldn’t have abandoned me.”

“I’m sure he does love you, just as much as you love him. But these are difficult times. We are all called upon to make impossible decisions and we don’t always get them right.”

“So you agree with me. Bunny shouldn’t have gone to France?”

“I’ve grown quite fond of him too, you know. But only Bunny can know what’s right for him. He’s younger than us. He wants to experience a little more of life before he settles down. You mustn’t worry. There’ll be a letter within a week and I’m sure he’ll be back before long.” Duncan stared at her like a child unconvinced by its parents efforts to arbitrate a sibling dispute.

At moments like this, and there were plenty of them, she wondered why she couldn’t stop loving him. She also knew that if anything happened to Bunny, far from opening up a path to what she really wanted, it would most likely drive Duncan into the arms of another man. The current ungainly triangle suited her purposes, any other might not be so manageable.

“I think I might join up after all,” he announced.

“After everything you’ve said? Are you mad?”

“I don’t think there’s much reason to stay here now, with Bunny gone.”

Vanessa could take no more; she knew Duncan would never enlist. “Bunny has not left you, Duncan. He’s gone to do something which should make us immensely proud of him.”

“You think you know him better than I do, don’t you?”

“I make no such claim, but I do know you, Duncan, very well. And I can’t stand it when you behave like this. Thousands of mothers and wives are receiving telegrams telling them their loved ones have been killed, and I bet every single one of them has taken the news with dignity. Look at you. Bunny’s probably having the time of his life, that’s what you can’t stand. You need to grow up.”

Duncan’s shoulders dropped and he slid down onto the floor, sobbing uncontrollably. She didn’t enjoy treating him like a child but sometimes it was the only way. In a few hours he would come and find her, she would seduce him and a little more progress would be made. She had hoped that Bunny’s departure would give her and Duncan the chance to spend more time alone together, but she hadn’t bargained on this reaction.

Thanks for reading Maynard’s War. Subscribe for free to ensure you never miss a chapter. Or take out a paid subscription to help me to deliver chapters on time.

And if you’re interested in all things Bloomsbury, and specifically 20th century British art, do check out Victoria K. Walker’s Beyond Bloomsbury. It’s fabulous.