Thanks for reading Maynard’s War, and a warm welcome to my new subscribers. Chapter 11 will be published next Sunday, 23rd February at 11am UK time. Do please share with anyone you think might be interested.

August 1915

It had taken longer than he had hoped, but Keynes was beginning to feel better, and getting through a reasonable quantity of work, dutifully fetched from the Treasury in tatty red boxes by Basil Blackett. It was nearly noon, the scheduled time of his visit from Vanessa to which he was greatly looking forward. He tidied away the last of the papers from the bedcovers. Once he’d mastered the knack of positioning his pillows correctly, he found working from the confines of his double bed rather efficient. Things seemed much closer to hand than they did on his huge desk at the Treasury.

He straightened his pyjamas and sat up as he heard Vanessa coming up the stairs, chatting away to Katherine, the young New Zealander to whom, on Bunny’s recommendation, he had let the attic rooms. “Do come in,” he said, as Vanessa knocked on the door. She pulled a chair over and sat beside him. Katherine asked if they’d like some lemonade – it was a stiflingly hot day – and disappeared to fetch it.

“I must say I thought you’d be looking worse, after all you’ve been through,” Vanessa began.

“I recovered quite quickly after the appendix operation, even started doing some work but then this damned pneumonia hit. Thank goodness my mother was here, and Katherine, of course, she’s been a great help.”

“She doesn’t look too well herself. Have you heard that cough?”

“I know. It’s a worry, but she says it’s nothing.”

“In any case, you are my priority for the time being. And I am bound to say, Maynard, you’ve been working too hard, that’s why you’ve been ill.”

“Yes, but I’ve always worked hard. If I didn’t I’d be bored.”

“Maynard.”

“I suppose I have been overdoing it a bit, especially since the change of government, but then it’s been a great deal easier working with McKenna. We had a marvellous time in Nice. It’s a gorgeous place. And we came back on a battleship.”

“The war certainly seems to give people the chance to experience things they wouldn’t in peace time,” she answered. “But it’s such a bloody tragedy. All these young lives.”

“I know. I still can’t believe Feri Bekassy has gone. It really was too awful to receive that news.”

“Yes, you and he were terribly close, weren’t you?”

“Some of the best days of my life, that summer I spent with him in Hungary. And I sent him to his death.”

“You did no such thing. Feri went home to fight for his country. Anyone would have done the same. It wasn’t his fault Hungary is on the wrong side.”

“Yes, but I gave him the money. I should never have let him go.”

“You really mustn’t blame yourself.” Vanessa took his hand in hers.

“I’d never lost anyone until all this started, but in the last year a dozen friends have lost their lives, all of them under thirty, it’s quite unbearable.” Tears covered his cheeks before he finished speaking.

“It is especially hard when they’re young. It was bad enough when my mother died, but far worse when we lost Stella. Twenty-eight and so full of life. And poor Thoby. I’m afraid those bereavements have left me rather cold about death. There seems so little one can do.”

“But I could have prevented Feri’s death. I can’t imagine what Noel Olivier must be feeling. Two months ago Rupert Brooke, and now Feri. She must be beside herself.”

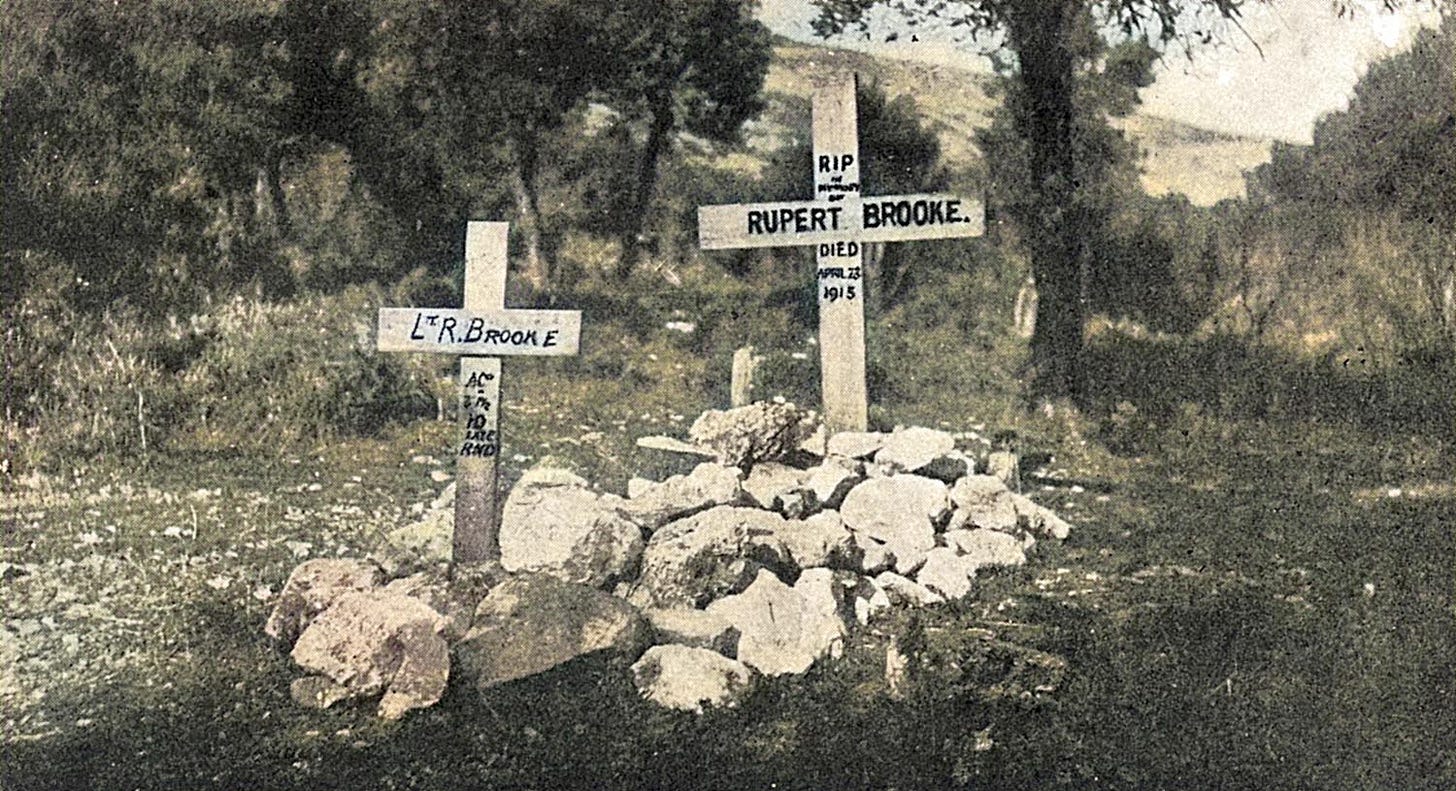

“Oh God, yes. I’d forgotten about her and Feri. Poor darling. I shall have to write. It’s funny though, how nobody had a good word for Rupert when he was alive, and now he’s the garlanded hero. The greatest poet never to have lived.”

“Vanessa don’t,” he said, unable to stifle a giggle. “We must show respect to those who have fallen, whatever we think of them, or of the cause in which they died.”

“I’m sorry, but Rupert was such a dreadful bore.”

“He was,” Keynes agreed, “at least he became so. He used to be such good company. At least dear old Freddie Hardman died actually fighting the enemy, with his bare hands apparently.”

“Poor Rupert wasn’t even afforded an heroic death.”

“No, but still a pretty ghastly one, by all accounts. We really must find a way to bring a rapid conclusion to this horrid war.”

The door opened and Clive came in carrying flowers and a bag bulging with books and provisions. “You’ve finally seen the light then Maynard?” he said, placing the bags on the bed before pulling up another chair.”

“Hello Clive, Vanessa didn’t tell me you were coming.”

“I wasn’t sure if I’d be back in time, but I was, and I managed to pick up these for you,” he pointed at the bags. “How are you old chap? We’ve all been very worried.”

“Much better, thank you.”

“We were just talking about how awful it is to lose so many of one’s friends,” Vanessa said to Clive.

“And Vanessa was being insufficiently respectful to poor Rupert.”

“I can imagine. He was too young to die though. I’ve been thinking about the parents of all these young men.” He looked across the bed to Vanessa. “Imagine if something happened to Quentin or Julian. It really doesn’t bear thinking about.”

“Clive, please.”

“Well,” Keynes said, “although I’ve had to revise my opinion over the likely duration of the war, I can assure you it will definitely be over by the time your delightful boys are of fighting age.”

“I should jolly well hope they’d refuse to fight, even if there was another war,” Vanessa said.

“Do you know,” Clive said, “I’ve never felt in such a minority. It seems there are only a dozen people in the entire country who oppose the war, and they’re all friends of ours.”

“We had another difficult weekend at Clive’s parents,” Vanessa explained. “Didn’t we darling?”

“Dreadful. Not just the glorification of death and suffering, but the way news of casualties spurs them on to ever greater spasms of patriotic fervour. I simply don’t understand how people can turn such a nightmare into a cause for celebration.”

“And then people accuse you of being an intellectual snob.” Keynes caught a twinkle in Vanessa’s eye as she said this.

“Oh, that Chesterton piece really was the limit,” Clive said.

Keynes held up his hands. “I know I wouldn’t have said it, even six months ago, but how anyone can argue against a negotiated peace now is quite beyond me.”

“They’d rather send thousands more young men to their deaths,” Vanessa answered.

“You know there’s a campaign to have my pamphlet banned,” Clive said. “It’s already been burned in the street. I can understand the argument that the Germans have to be resisted, but to censor the opinions of people opposed to the war, it’s intolerable.”

“And Clive’s father has stopped his allowance because of the shame his pacifism has brought upon the family.”

“Oh, he’ll calm down. In any case, Maynard can always lend us a few quid if things get tight,” he said, smiling.

“Don’t be afraid to ask. I seem unable not to make money at present. Only too happy to help out friends in difficulty, especially you two. Everything is alright, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” they answered together, before Clive gave way.

“We plough our separate furrows, but we enjoy each other’s company,” Vanessa finished.

“I think it rather civilized,” Clive added. “For so many couples, marriage becomes a routine. This way things remains fresh. Didn’t we always say we mustn’t allow convention to dictate the way we live?”

“I’m not sure our youthful convictions necessarily took full account of the complexities of the human heart,” Keynes replied.

“Oh, I don’t know,” Clive said, apparently not wishing to engage further.

“And how is Duncan?” Keynes asked.

“He’s in a bit of a state,” Vanessa replied. “Bunny’s gone to France to volunteer and Duncan hasn’t heard a thing in nearly three weeks. I’m sure Bunny’s just too busy to write, but Duncan takes these things so personally.”

“I assume he’s not thinking of enlisting?”

“He keeps threatening it, but he won’t.”

“I’m sure you’re right,” Keynes agreed, “although it may not be long until all men of fighting age are compelled to join up.”

“They wouldn’t bring in conscription until it was absolutely necessary, surely?” Vanessa asked.

“Politicians like to be seen to be taking tough decisions in times of crisis. And it would play well with the families of those who have already volunteered.”

“And who do you think will be included?”

“I think it likely we’ll all be caught in the net. Even Lytton and Leonard.”

“God help us if Lytton is sent to the front,” Clive said.

“I suppose he might confound the Germans into surrender,” Keynes answered, laughing.

“You’ll be alright though,” Clive said. “I can’t see the Treasury sending it’s best brain to take a bullet.”

“Let’s hope so. Not that I’ve been much use to the nation’s finances these last few weeks.” There was a pause before Keynes decided to change the subject. “I hear Virginia has been rather unwell again.”

“Oh it’s awful,” Vanessa answered. “Quite as bad as ever. She won’t have Leonard in the room, and she’s attacked the nurses on several occasions.”

“How dreadful. She seemed so well when I last saw them, certainly nothing to suggest another breakdown. And with her novel just published.”

“It’s really rather good,” Clive said, reaching into one of the bags and pulling out a book. “I bought you a copy.”

“Thank you Clive.”

“I rather fear it’s the book that’s done for her,” Vanessa said. “I know we artists are sensitive creatures, but worrying about her writing seems to push Virginia over the edge.”

“Leonard thinks she’s a genius. He’s convinced she’s going to be a great writer,” Keynes said, thumbing through the book.

“That’s the one thing Woolf and I agree on. There’s something in that,” Clive said, pointing to the book. “Writing is like painting. It’s the progression in an artist’s work that ultimately defines their achievement. This may not be a great work of literature, but it suggests to me there are great works to come, if only she can remain well.”

“Leonard seems determined to do whatever is necessary for Virginia to write,” Keynes said.

“I suppose he may have her best interests at heart. But I still don’t understand why she married a Jew,” Clive said, seemingly from nowhere.

“Oh Clive, don’t start.” Vanessa said.

“What? She says it herself. I married a penniless Jew. She’s laughs about it.”

“She’s also told us how much she loves him,” Vanessa said crossly.

“She thinks the same of those people as I do, and as you would if you’d only be honest with yourself. You should hear her talk about Woolf’s family. She abhors them.”

“And how would you know what I really think?” Vanessa gave him a withering look.

“I haven’t met Leonard’s family,” Keynes said, “but I suspect Virginia’s dislike of them is more to do with class than religion or culture.”

“Rubbish,” Clive replied, without a great deal of conviction.

“And where’s the rational basis for your belief, Clive? Good old fashioned prejudice. Did you learn nothing at Cambridge?” Keynes was not going to let him off the hook.

“I think it’s time we were going,” Clive said, looking at Vanessa.” I wish you well in your recovery Maynard. Goodbye.” With this he left the room.

Instead of following him, Vanessa looked at Keynes and they both started to giggle. “I suppose I ought to go with him,” she said. “Funny isn’t it? He spends so much time urging people to defy convention and find new ways of living, yet he has a total blind spot when it comes to the oldest prejudice of all.”

“At least we know that Virginia is in the best possible hands,” Keynes said, picking up the book and looking at the spine. ‘The Voyage Out,’ he said, “ I shall enjoy reading this.”

Thanks for reading Maynard’s War. Subscribe for free to ensure you never miss a chapter. Or take out a paid subscription and help me to deliver chapters on time.

And if you’re interested in all things Bloomsbury, and specifically 20th century British art, do check out Victoria K. Walker’s Beyond Bloomsbury. It’s fabulous.