Thanks for reading Maynard’s War, and welcome to my new subscribers. I hope you enjoy this latest chapter. Chapter 9 will be available next Sunday, 9th February at 11am. Please do share with anyone you think might be interested. It takes but a moment to click ‘like’ or ‘restack’.

April 1915

The trip to Paris had been a success. Keynes had been able to show off his excellent grasp of international finance and helped negotiate a satisfactory agreement. But it had meant rearranging his visit to the Woolfs in Richmond, so two days after he got back, he finished work early and boarded a train at Waterloo. He asked directions at Richmond Station and, after a short walk, Leonard himself answered the door.

As they made their way upstairs, Leonard explained that their lodgings were temporary; their new home not yet being ready to move into. Reaching the second floor, Keynes was shown into a serviceable sitting room. Leonard took his coat before pouring them each a glass of sherry and indicating to Keynes to take the chair closest to the fire.

“How was Paris?” Leonard asked.

“Cold, but worthwhile.”

“You know I’ve been back from Ceylon four years now, and I still can’t get used to the weather. What was the purpose of the trip?”

“How we pay for the war, essentially. Top level meetings with the French and Russian Finance Ministers.”

“Was Lloyd George with you?”

“Yes,” Keynes smiled. “He was leading the delegation, Cunliffe and Montagu in support, Blackett and I doing the real work behind the scenes.”

“And how does the Chancellor find taking advice from a young Cambridge don?”

“He’s getting used to the idea, slowly.”

“Not the easiest man to get on with from what I’ve heard.”

“Par for the course with politicians. I only wish they’d focus on the things they’re good at and leave the technical side of things to the experts.”

“But are the experts up to the task?”

“Fair point. At least Lloyd George has a good brain, unlike some of the people around him. I can only assume Oxford bestows its honours more freely than Cambridge.”

“No pangs of conscience then, about using your expertise to help the allies figure out how to finance the war effort?”

“I’m not sure it’s the time for conscience, Leonard. The politicians contrived to get us into this miserable war, now someone has to ensure we come out of it on the winning side. If that task falls to me then so be it. I don’t think it’s going to last that long, in any case. Now tell me, how is Virginia?”

Leonard moved towards the fireplace and touched the wooden mantle. “She’s well, I think. She’ll be down shortly.”

“Good. Vanessa said she seemed much better.”

“Yes, certainly on the surface. But it’s difficult to gauge. That’s why we missed your dinner the other week. I don’t want to take any risks until I’m sure she’s absolutely well.”

“I completely understand. We did have rather a good evening though. Duncan especially, with his new beau.”

“Oh yes, young Garnett. Bunny or whatever he calls himself. I saw them at Lytton’s over Christmas. They made me feel rather old. Not their behaviour so much, rather their attitude towards me: strangely formal. What happened to us Maynard? Are we not young any more?”

“I’m not quite as ‘not young’ as you, but I do know what you mean.”

“And what does Vanessa think of this business with Garnett?”

“She’s not really able to be honest about her feelings for Duncan, not with me anyway. But she and Duncan are rarely apart, except when he’s with Bunny.”

“And what of Clive?”

“Still carrying on with Mary Hutchinson as far as I know. There may be others of course. But he, Vanessa and Duncan appear to get on well enough.”

“I do hope Vanessa is happy. I wonder about these arrangements though,”

Before he could finish, the door opened and Virginia came in. “And what arrangements are these?” she asked.

“Virginia, how lovely to see you.”

“Thank you Maynard. I’m delighted to see you too. It’s been far too long. Have you been busy?”

“Only in the last month.”

“Yes, Leonard told me, you have a new job. Is it interesting?”

“Yes, it’s good to be at the heart of things again.”

“I can ask you lots of questions about the war, then.”

“Well, I do spend a great deal of time with senior members of the government, so by all means fire away.”

“How long is it going to last?” she asked, in a tone that suggested she expected a definitive answer.

“Not as long people seem to think. We are bound to win, and in some style. There was a great deal of shilly-shallying at the outset, but now that we’ve applied ourselves properly to the problem, it really shouldn’t be too long.”

“But presumably the Germans are applying themselves with at least equal efficiency?” Leonard asked.

“Between the three of us, German finance is crumbling,” Keynes answered.

“I hope you’re right. I’ve been surprised at the appetite for war on both sides,” Leonard said.

“If you’d asked me a year ago I would have said war was impossible. One look at the economic situation should have persuaded anyone of that,” Keynes added.

“But nobody much bothered with the economic realities,” Leonard said.

“No.”

“So,” Virginia began, “you both misread the situation completely. At least I have the excuse of not really engaging with politics, but you two were fully immersed and still you missed it.”

“We did, and for that we can only apologise,” Keynes said, sheepishly.

“Did nobody in government realise the folly of going to war with so small an army compared with that of the Germans?” Leonard asked, irritated that Keynes had included him in his apology.

“They felt they had no choice. There was no time to consider the practicalities, an immediate response was called for.”

“Why is it,” Virginia asked, “that when politicians are presented with the choice of war or no war, they always choose the former. Could it be something to do with the fact that they are all men?”

“There is probably some truth in what you say,” Leonard answered, “but the question now is what can be done to bring it to an end?”

“I don’t imagine that’s of much concern to Maynard, given his new job.”

“That’s rather unfair, Virginia. I would prefer not to be at war, but things happen for a reason. I’m afraid the war will have to take its course. Trying to stop it would be like trying to rewrite history.”

“Surely you’re not suggesting we shouldn’t exhaust all possible means to end the war?” Leonard asked.

“You can exhaust all the means you like. I’m just not sure it’ll make any difference. This war will not be ended by diplomacy, only when one side goes broke. But as I said, that shouldn’t be long.”

“And if you’re wrong.”

“I can only base my judgement on things as I see them, Leonard. My best estimate is that the war will be over by summer. In the meantime, I will direct my energies to ensuring we emerge victorious.”

“But you just said there was no point trying to influence the outcome,” Virginia said, raising an eyebrow in Leonard’s direction.

“Confound it Virginia. I hate the war as much as you do. But the best way to guarantee victory is to make sure we have the funds to fight off the aggressor.”

“And that’s what you’re doing at The Treasury, making sure we don’t go bankrupt before they do?” she added, clearly enjoying herself.

“Exactly.”

“With the likely outcome,” Leonard said, “if your information about German finance is not correct, of ensuring the war drags on for years.”

“Really Leonard, what would you have me do? I have offered my services to the government at a time of acute national crisis. What, precisely, are you and your socialist friends doing about the damned war?”

“Actually, Leonard and his socialist friends are doing a great deal, aren’t you Mongoose?”

“We’re doing what we can, yes.”

“Don’t be so modest. Tell Maynard about the research you’re doing.”

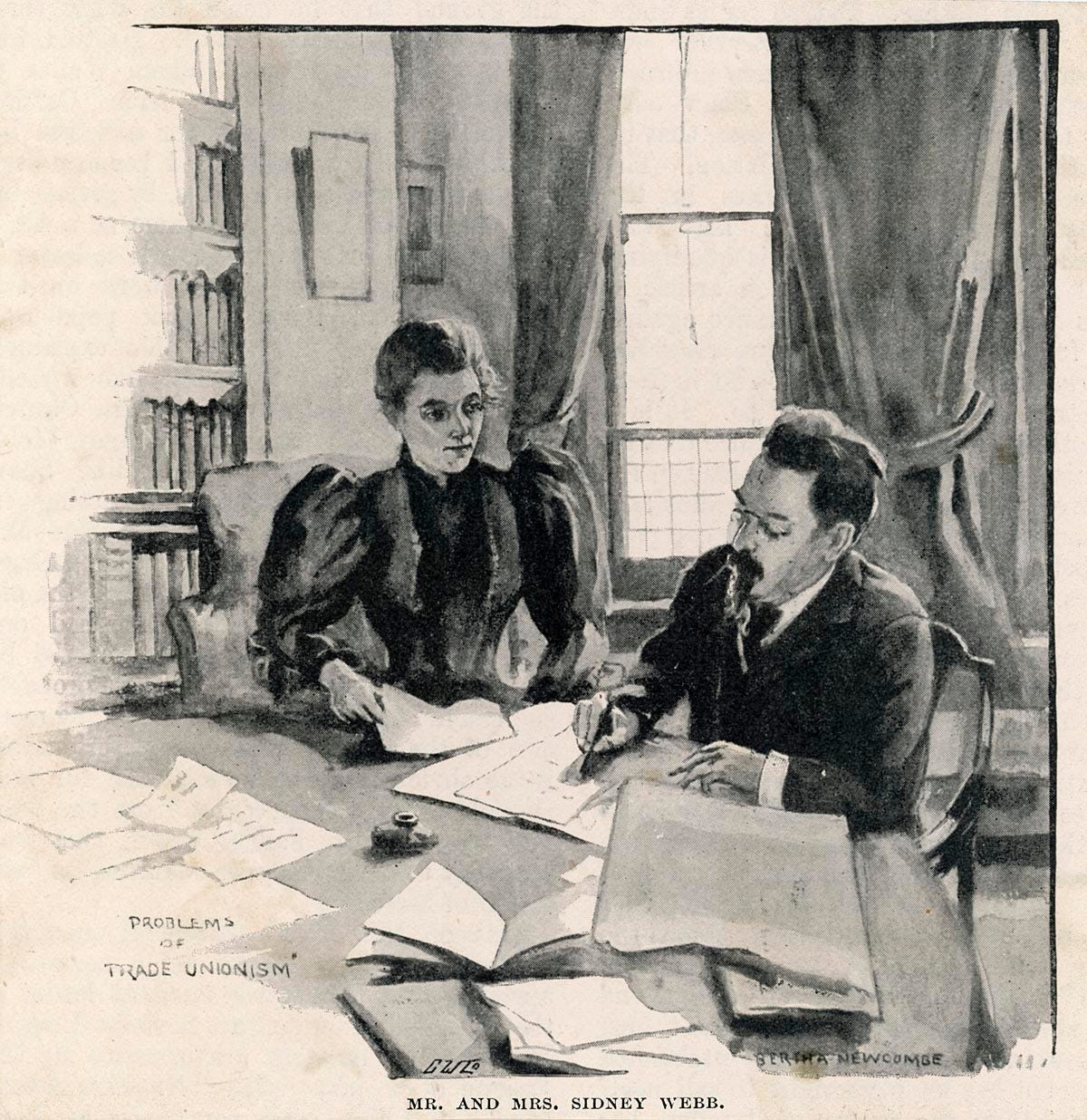

“Oh well, yes. Beatrice and Sidney Webb have asked me to write something on the prospects for the international supervision of foreign policy and arms control, with a view to preventing future wars.”

“Hasn’t the horse rather bolted?” Keynes asked bluntly.

“Once this sorry war is over we’re going to need institutions in place to make sure it can’t happen again.”

“International institutions?” Keynes asked, sarcastically.

“Yes. I have in mind some kind of league to which all nations are affiliated.”

“Sounds marvellous, but I can’t imagine it’ll ever happen.”

“Well perhaps the Webbs are a little more ambitious for the future than you are Maynard. Although I must say, they are a little peculiar.” Virginia said.

“That’s putting it mildly,” Keynes agreed.

“They are somewhat lacking in the social niceties,” Leonard admitted. “But they do bring a missionary zeal to politics, and it does draw people in.”

“But socialism?” Keynes said, feigning exasperation. “It’s such a dull doctrine, and so devoid of any logic. I sometimes wonder if Marx ever met an actual human being. I know capitalism has its problems but socialism, really?”

“As you well know, Maynard, the Webbs are not Marxists, they are Fabian socialists,” Leonard answered.

“Ah yes, Fabius Cunctator: take no risks and see what happens.”

“There’s something to be said for picking your moment, especially if you’re looking to change society fundamentally,” Leonard responded.

“Quite possibly, but old Fabius was hardly the most successful of Roman generals, was he?”

“So you’d put yourself in the Marxist camp, would you Maynard?” Virginia said, jumping to the defence of her husband.

“No. I’m no kind of socialist at all. But look at the Fabians’ agenda: a minimum wage, universal healthcare, the abolition of hereditary peerages. Mark my words: none of these will come to pass in my lifetime.”

“But they could,” Leonard implored, “especially if they had the support of someone in a position of influence, like you.”

“Do you really think the state could effectively intervene in the market to ensure everybody has access to decent medicine?”

“Yes, I think in a democracy that is exactly what the state should be doing.”

“But the distribution of wealth in society is a given. Always has been.”

“That doesn’t mean it can’t be changed.”

“So you plan to abolish the entire class system do you? I admire your idealism but do you not think it rather misplaced, especially now?”

“Not at all. I think now is precisely the time for idealism. Indeed, it’s possibly our only hope.” Leonard answered, walking over to the window. He was determined not to get into a verbal spat he was unlikely to win. He would leave the next move to Virginia.

“Do you think women will get the vote in your lifetime Maynard?” she asked.

“The way things are going I suspect they might, yes.”

“And would that be a good thing?”

“I think it would, yes. It would certainly shake up the political establishment.”

“But don’t you see Virginia’s point?” Leonard asked, returning from the window.

“Point?”

“The point is that nothing changes unless people agitate. Unless people talk about the possibility of a different kind of world. Sometimes one needs to shout in order to get one’s opinions heard.”

“I have no problem with people giving voice to their opinions. I just can’t see Beatrice and Sidney Webb leading us into a golden age of peace and prosperity.”

“I agree, the Webbs are not cut out for public life. But what they have done is give birth to the notion that moral values and a sense of progress have a place in politics.”

“So you’re throwing your lot in with the Fabians?”

“I am. Until I become established, it’s useful to have a sponsor, and for all their foibles the Webbs are very well connected.”

“So you also plan to write for a living?”

“It’s one possible source of income, yes.”

Keynes knew better than to deliver his next line, something about two struggling writers in the same household. Instead he allowed Leonard to refill his glass.

“Now, Maynard,” Virginia said, “there must be some gossip to catch up on. I feel so detached out here in Richmond. I long to be back in London with my friends.”

“Well, as I was saying to Leonard, most of the gossip concerns your sister’s love life.”

“Do you think I should worry about her? Part of me thinks there must be something wrong, but then I remember what she was like growing up and it doesn’t surprise me that she’s so restless. I imagine she’ll keep moving from man to man until she finds one she can’t outgrow.”

“Too many people settle for second best,” Keynes said.

“So it’s definitely over with Roger?”

“Certainly as far as she’s concerned. He’s struggling to come to terms with it by all accounts.”

“I do feel sorry for him. He’s such a brilliant man. All that trouble with his wife, and now this. He really deserves better.”

“You think Vanessa would be better off with Roger than with Duncan?” Leonard asked Virginia.

“I don’t know, but Roger was so good to her after Quentin was born.”

“He was certainly a darn sight more supportive than Clive.” Leonard said.

“Yes, but you can’t blame Clive for that,” Virginia snapped.

“He’s her husband, for God’s sake. Surely if a woman is struggling to cope after childbirth, then it’s a husband’s job to give all the support he can, instead of spending every night with somebody else’s wife.”

“You’re exaggerating Leonard.”

“He may be exaggerating, but only slightly,” Keynes said. “Clive’s behaviour was pretty reprehensible.”

“Perhaps,” Virginia was irritated, “but that doesn’t detract from the fact that my sister seems rather fickle in her liaisons. And it worries me that Duncan thinks only of himself.”

“As you have found to your cost, Maynard,” Leonard added.

“Now it’s my turn to defend the indefensible. Duncan is a very complex character. He’s also deeply attractive in ways that are difficult to understand, unless, well, unless you have experienced the power of that attraction.”

“Oh poor Maynard,” Virginia said. “First the man you love goes off with my brother, and now he’s gone off with my sister. We do love you, you know, even if my siblings have a funny way of showing it.”

“I don’t blame your sister at all. I just hope Duncan will be kind to her.”

“Keeping his hands off Bunny Garnett would be a start,” Leonard suggested.

“Yes,” Keynes agreed.

“Why do people make things so complicated for themselves?” Leonard asked nobody in particular.

“Not everyone. You two are an example to us all.”

“We are very happy aren’t we Mongoose?” Virginia said.

“Yes, we are my love.”

Thanks for reading Maynard’s War. Subscribe for free to ensure you never miss a chapter. Or take out a paid subscription to help me to deliver chapters on time.

And if you’re interested in all things Bloomsbury, and specifically 20th century British art, do check out Victoria K. Walker’s Beyond Bloomsbury. It’s fabulous.